Glasgow's Square Mile Of Science

by Ian R. Mitchell

Many will be familiar with the book by Jack House, Square Mile of Murder, which recounts the lust and lucre-motivated nefarious goings on amongst some of the middle class denizens of Glasgow's West End in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But there was more than murder and mayhem occurring in the grand terraces of the bourgeoisie at that time, and one could just as easily write a book on the area entitled Square Mile of Science. This is beyond the scope of the present article, which will instead take the reader on a virtual tour of some of the sites in the area associated with scientific achievement, in the hope he or she may be persuaded to undertake a real ramble in what was, till WWI, Glasgow's most salubrious quarter.

Many will be familiar with the book by Jack House, Square Mile of Murder, which recounts the lust and lucre-motivated nefarious goings on amongst some of the middle class denizens of Glasgow's West End in the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. But there was more than murder and mayhem occurring in the grand terraces of the bourgeoisie at that time, and one could just as easily write a book on the area entitled Square Mile of Science. This is beyond the scope of the present article, which will instead take the reader on a virtual tour of some of the sites in the area associated with scientific achievement, in the hope he or she may be persuaded to undertake a real ramble in what was, till WWI, Glasgow's most salubrious quarter.

Starting at Hillhead Subway, south down Byres Road takes you to University Avenue, where the first object to meet the eye is a massive concrete clad building in the now unpopular architectural style of the early 1970s. This was named after John Boyd-Orr, born in 1880 in Ayrshire, who graduated BSc Glasgow in 1910, and worked in the University's Physiology Dept before moving to the Rowatt Institute, Aberdeen, in 1923. There he studied animal and human nutrition, and laid the basis of government policies during WWII and afterwards. Boyd-Orr was the first Director of the UN Food and Agricultural Organisation 1945-48. He was also a supporter of nuclear disarmament, and a founder member of CND. Awarded the Nobel Peace Prize 1949, he was Rector (1945) and Chancellor (1946) of Glasgow University, and died in 1971.

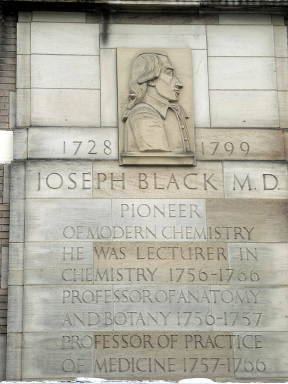

Rather more pleasing on the eye is the Chemistry Building across the road on University Place, a brick-built construction from the 1930s. On the wall is a large plaque commemorating Joseph Black. Born in Bordeaux in 1728 Black studied at Glasgow University under Cullen, and at Edinburgh. His M.D., described as the most original graduation thesis every written, was the first scientific identification of a gas, carbon dioxide, which Black called "fixed air." He was appointed to the Chemistry chair at Glasgow in 1756 where he completed his most important work, the discovery of both "latent and "specific" heat. Black had a lucrative industrial consultancy and helped James Watt's researches on the steam engine with finance and scientific advice. An inspired teacher, hundreds attended his lectures. He later moved to Edinburgh University, but did no further important scientific work there. Black is seen as the father of modern scientific chemistry.

A little uphill along University Avenue and we come to the wrought-iron Memorial Gates from 1951, the 500th anniversary of the University's foundation. Amongst the many luminaries from all disciplines honoured there is William Cullen, Black's teacher. Born in Hamilton, he matriculated at Glasgow in 1726 later setting up in medical practise. He taught chemistry at Glasgow 1744-51, then took over the Chair of Medicine in the University. In 1756 moved to more prestigious Edinburgh medical chair. A classifier rather than a man of original discoveries, Cullen no longer has the huge reputation he had in his lifetime.

A few steps inside the memorial gates and we come to the Hunterian Memorial. The Hunter brothers William (b.1718) and (John b.1728) were Britain's most eminent medical practitioners in the eighteenth century. William left Glasgow University (where he studied with Cullen) in 1736 without a degree, though he was awarded an MD by the University in 1750. He is regarded, with his Description of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774) as the founder of gynaecology and developed a high class London practise (including royalty) which made him a very rich man. On his death he left £5000 to Glasgow University to build a museum for his collections. The Hunterian Museum is now one of the University's star attractions, and lies in the main building behind the memorial. John didn't attend any University, nevertheless he developed as a highly skilled surgeon in London, where he endowed another Hunterian Museum.

A few steps inside the memorial gates and we come to the Hunterian Memorial. The Hunter brothers William (b.1718) and (John b.1728) were Britain's most eminent medical practitioners in the eighteenth century. William left Glasgow University (where he studied with Cullen) in 1736 without a degree, though he was awarded an MD by the University in 1750. He is regarded, with his Description of the Human Gravid Uterus (1774) as the founder of gynaecology and developed a high class London practise (including royalty) which made him a very rich man. On his death he left £5000 to Glasgow University to build a museum for his collections. The Hunterian Museum is now one of the University's star attractions, and lies in the main building behind the memorial. John didn't attend any University, nevertheless he developed as a highly skilled surgeon in London, where he endowed another Hunterian Museum.

We drop downhill to the Pearce Lodge at the foot of University Avenue, and here encounter a charming seventeenth century gatehouse, re-assembled from the High Street whence the University moved to Gilmorehill in the 1870s. Through these gates walked those we have already discussed, as well as Colin MacLaurin, who was born at Glendaruel, Argyll in 1698. He graduated MA from Glasgow at the age of 16 with a thesis in defence of Newton's ideas of Universal Gravitation. At 19 he was Professor of Mathematics at Aberdeen University, later moving to Edinburgh. He was a friend of Newton and a lifelong defender of his ideas, namely in his Theory of Fluxions (1742). He was also an original mathematician and Maclaurin's Theorem is still taught today. MacLaurin died of pneumonia in 1746 after organising Edinburgh's defences against the Jacobites, and then fleeing to England.

Just opposite the Pearce Lodge on University Avenue is the Rankine Building, another rather uninspired construction from the later 1960s. Glasgow established the world's first Chair of Engineering in 1840, and the building is named after its second incumbent. Rankine worked as an industrial engineer beforehand. He continued this when an academic, consulting on the Loch Katrine water supply, designing 'Tennants Stalk', working on metal fatigue and becoming first president of the Institute of Engineers in Scotland. His main theoretical work was on fluid dynamics to do with the shipbuilding industry (Shipbuilding Theoretical and Practical 1866) and more especially thermodynamics: the convertability of heat and work. He wrote the Manual of the Steam Engine (1859) and elaborated the 'Rankine Cycle' to describe its workings. Rankine worked with Kelvin on laws of thermodynamics and some feel he should have greater recognition in this than he has been awarded. He died in 1872, aged only 52.

If we turn right down Kelvin Way after a few hundred yards we come to a delightful part of Kelvingrove Park, with the University tower looming over us. Here we encounter a fine pair of bronze public sculptures, the first being Shannan's 1913 statue of Lord Kelvin (William Thomson) executed six years after the scientist's death. Born in 1824 in Belfast, Thomson moved to Glasgow in 1832 when his father was awarded the Mathematics chair at the University. Educated by his father and at Cambridge University, Thomson was appointed to the Natural Philosophy (Physics) chair at Glasgow in 1846, a post he held for 53 years. Like many scientists he did his best work young, being involved in the elaboration of the fundamental laws of thermodynamics in the early 1850s. He was offered the Cavendish chair of Physics at Cambridge in 1871 and refused it, in order to stay in Glasgow. Later Kelvin's involvement in industrial consultancy and his economic activities (he held 70 patents at his death) overshadowed his scientific work. His compass was adopted by the Admiralty in 1889, before which he was the brains behind laying the first successful transatlantic cable in 1866. Ennobled as Lord Kelvin, he died with a fortune at today's values of £10 million. Regarded by the Victorians as the epitome of the successful scientist, Kelvin is buried beside Newton in Westminster Abbey. Today however his reputation has fallen.

Though Kelvin set up teaching laboratories at the new Gilmorehill campus, and trained many competent practical scientists, he established no research laboratories or programme, and his 50 year tenureship stultified the Natural Philosophy Department. Despite his own work in electro-magnetism in the 1840s Kelvin opposed Maxwell's electro-magnetic theory of light, opposed the new physics based on X-rays and sub atomic particles, and opposed the geologists uniformitarianism, behind which he saw evolutionary Darwinian anti-Christian ideas lurking. In 1850 Glasgow was at the head of physical research in the UK; in 1900 it was way behind UCL, Cambridge and Oxford. Kelvin was to an extent responsible for this. (See Degrees Kelvin, David Lindley (2004))

In the eighteenth century Glasgow scientists (Cullen, Black, MacLaurin) took part in a brain drain to the more prestigious Edinburgh. In the nineteenth century the University's increasing reputation not only held onto Glasgow men like Kelvin, but also attracted practitioners of science from elsewhere (Rankine was from Edinburgh). A good example was Joseph Lister, whose memorial stands a little downhill from Kelvin's. Paulin's 1923 statue of Joseph Lister (b.1827) commemorates his time as Professor of Surgery at Glasgow 1860-9, when the University was still in the High Street and the attached hospital was the Royal Infirmary, where Lister did his famous experiments on antisepsis. Reading Pasteur in 1865 convinced Lister that infection came from miasma in the air, and he developed carbolic acid sprays as an antidote. Later it was established that infection came from many more areas than the air, and others working at the time had as good results as Lister in patient survival, but Lister retains the fame. Crossing Kelvin Way a walk through the delightful Kelvingrove Park takes you to Woodside Place, where at No. 17 there is a plaque on the wall, commemorating Lister's residence in Glasgow, a house where he apparently gave the most frugal and dull dinner parties.

In the eighteenth century Glasgow scientists (Cullen, Black, MacLaurin) took part in a brain drain to the more prestigious Edinburgh. In the nineteenth century the University's increasing reputation not only held onto Glasgow men like Kelvin, but also attracted practitioners of science from elsewhere (Rankine was from Edinburgh). A good example was Joseph Lister, whose memorial stands a little downhill from Kelvin's. Paulin's 1923 statue of Joseph Lister (b.1827) commemorates his time as Professor of Surgery at Glasgow 1860-9, when the University was still in the High Street and the attached hospital was the Royal Infirmary, where Lister did his famous experiments on antisepsis. Reading Pasteur in 1865 convinced Lister that infection came from miasma in the air, and he developed carbolic acid sprays as an antidote. Later it was established that infection came from many more areas than the air, and others working at the time had as good results as Lister in patient survival, but Lister retains the fame. Crossing Kelvin Way a walk through the delightful Kelvingrove Park takes you to Woodside Place, where at No. 17 there is a plaque on the wall, commemorating Lister's residence in Glasgow, a house where he apparently gave the most frugal and dull dinner parties.

Now we are in the heart of nineteenth century bourgeois Glasgow, the Park district where lived the captains of industry, academics and clergymen of the city's elite in their fine Victorian terraced houses, set back from private gardens, laid out between 1830 and 1860 far from the squalid and overcrowded East End. The Park area possibly the finest piece of Victorian town planning in the UK, but sadly at the end of Woodside Place, when we come to Woodside Terrace, a dreadful office block stands where Nos 1-5 Woodside Crescent used to be. However, No 10 still stands, and here we come to the Hooker residence, and a plaque on the wall commemorates William Jackson Hooker who became the Professor of Botany at Glasgow University in 1820, aged 35. A rich, enthusiastic amateur who had "never lectured nor attended a lecture" he transformed the Botany Department, increasing student numbers and the size of its collection. Though not opened till the year after he moved to become first full time director at Kew Gardens, Hooker was responsible for the development of the Botanic Gardens on Great Western Road. He also wrote Flora Scotica (1821). Surprisingly the memorial does not mention Hooker's more famous son.

Though born in Suffolk in 1817 John Dalton Hooker attended Glasgow High School and then graduated MD at Glasgow University in 1839. He subsequently went on a long Arctic voyage in the Erebus and wrote Flora Antarctica (1844-7), which was followed by another journey to Sikkim which resulted in Rododendrons of the Sikkim Himalaya (1849-51). Hooker's plant researches gave evidence for the ideas on natural selection and he was the first person in whom Charles Darwin confided his ideas on evolution, and one of the first to champion Darwin's ideas in public. On his father's death in 1865, J.D. Hooker was appointed as director at Kew. Though not commemorated at the house in Woodside Crescent, the profusion of rhododendrons in the private gardens of Park are an ironic memorial to him.

Moving on we come to the pillared porticoes of the mansions of Woodside Terrace, and at No 3 lived till his death in 1924, William MacEwan. Born in Bute in 1840, MacEwan was Britain's greatest nineteenth century surgeon, as the Hunters had been in the eighteenth. He studied under Lister at the Glasgow Royal Infirmary and later became Regius Professor of Surgery at Glasgow; (MacEwan turned down a move to John Hopkins University in the USA in 1889, again showing that Glasgow was able in the nineteenth century to hold attract, and retain, the best scientific and medical practitioners). Macewan carried out the first brain tumor removal and the first open-chest operations, proving that this did not cause the lungs to collapse as well as pioneering bone transplant surgery.

By the time of MacEwan's death in 1924, Glasgow's economy was in decline and so was the Park area as rich people moved to the suburbs, and town houses were converted to offices, hotels and sometimes to more dubious usages. In the last twenty years this process has been reversed and more and more town house are being converted to up-market flats. On the next stage of our walk however, this has not yet happened and the area has a demotic rather than a bourgeois, air to it. Half way along Woodside Terrace a right turn takes you to Lynedoch Street where you drop down, cross Woodlands Road and follow Ashley Street to West Princes Street. On the right across the road is Queens Crescent, formerly one of Glasgow's most prestigious addresses when it was built in the 1840s. The street is now sadly delapidated, with some houses lying derelict, though surprisingly the private gardens are still in good condition. Here, at No 2 was the birthplace of one who many would regard as Glasgow's greatest ever scientist.

By the time of MacEwan's death in 1924, Glasgow's economy was in decline and so was the Park area as rich people moved to the suburbs, and town houses were converted to offices, hotels and sometimes to more dubious usages. In the last twenty years this process has been reversed and more and more town house are being converted to up-market flats. On the next stage of our walk however, this has not yet happened and the area has a demotic rather than a bourgeois, air to it. Half way along Woodside Terrace a right turn takes you to Lynedoch Street where you drop down, cross Woodlands Road and follow Ashley Street to West Princes Street. On the right across the road is Queens Crescent, formerly one of Glasgow's most prestigious addresses when it was built in the 1840s. The street is now sadly delapidated, with some houses lying derelict, though surprisingly the private gardens are still in good condition. Here, at No 2 was the birthplace of one who many would regard as Glasgow's greatest ever scientist.

William Ramsay was born in 1852 into a scientific-engineering family background, and graduated from Glasgow before doing his Ph.D in Germany (then a one year degree) in 1872. Ramsay taught chemistry at Glasgow till 1879, then moved to Bristol and finally to the Chair at University College London in 1887. He established a research programme at UCL with a strong team to fill in the gap in Mendeleev's Periodic Table of the elements, discovering in the process the so called inert gases of argon, helium, krypton and zenon. For this he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1904. He then studied the recently discovered phonemena associated with radioactive decay. With Frederick Soddy at UCL Ramsay showed that radon decay produced helium nuclei, the very first experimental verification of the transmutation of elements. Soddy himself later moved to the Chemistry Dept. at Glasgow and in 1912 demonstrated the existence of radioactive isotopes, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1921.

We end our square mile of science here, ironically close to where Jack House ended his square mile of murder with the grizzly end of Marion Gilchrist in West Princes Street, for which Oscar Slater was framed. Hopefully Queen's Crescent will undergo restoration before it is too late, and we may one day see a memorial to Ramsay at his birthplace (there is one in the Bute Hall in the University). The Subway led us to the start of our trail; a few steps from Queens Crescent St George's Cross station allows the Subway to bring it to an end.