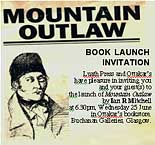

The Officer - from Ian R. Mitchell's 'Mountain Outlaw'

Ian R. Mitchell's latest book 'Mountain Outlaw', the story of Ewan MacPhee Scotland's last bandit, has received an enthusiastic and immediate response from the media since it was launched on 25th June, 2003. The Scotsman, the BBC and Aberdeen's Press and Journal are a small example of those intrigued by the existence of a bandit in the middle of the 19th century. Folk in Glengarry, Lochaber - Macphee territory - have already been entertained by Ian with readings from 'Mountain Outlaw' and local people are very keen to keep the name of their local legend alive.

Ian R. Mitchell's latest book 'Mountain Outlaw', the story of Ewan MacPhee Scotland's last bandit, has received an enthusiastic and immediate response from the media since it was launched on 25th June, 2003. The Scotsman, the BBC and Aberdeen's Press and Journal are a small example of those intrigued by the existence of a bandit in the middle of the 19th century. Folk in Glengarry, Lochaber - Macphee territory - have already been entertained by Ian with readings from 'Mountain Outlaw' and local people are very keen to keep the name of their local legend alive.

Ian's first novel looks likely to be a great success - he has received numerous awards for his 'mountain writing' books and in Ewan MacPhee he has revealed a fascinating character. There's nothing quite as attractive as a 'good baddie'.

Could make a perfect film role for Ewan MacGregor .....

The Officer

The deposition of Major-General Mackay, made to the Court martial in absentia of Ewan MacPhee, 12 August 181-.

I will be brief and to the point, as none of the matters of which I intend to speak are in dispute.

I first met the man designated Ewan MacPhee on the occasion of his enlistment along with several other members of the various tribes of that upland region of Lochaber called Glengarry. That some of these men had been forcibly enlisted I knew, but as a soldier felt that none of my concern, which was to ensure that they were trained and equipped to go and fight Bonaparte wherever the needs of current warfare dictated. Accordingly I joined up with these recent recruits at Stirling Castle sometime in the winter of the year 180-.

My new Highland charges were outstanding specimens of manhood, convincing me again of the wisdom of enrolling the surplus population of these desert regions into the military. With a health and vigour which the recruits from our manufacturing districts do not possess, and with an acute intelligence that our agricultural labourers lack, they provide (when properly led) excellent soldiery, lacking only that essential quality of leadership potential, and thus disqualifying themselves from consideration for the higher offices of the Army. However, improvement in their education and society may yet rectify this deficiency.

Even amongst these men, MacPhee stood out, not only by his stature and obvious strength, but additionally by his demeanour which, though difficult to pin down as insubordination, had something of the haughty and the arrogant in it, a quality lacking in his more docile compatriots. Though I kept a careful eye on him in training, he gave me no cause for complaint,and indeed I could quickly see that - though incapable of commanding anything such as a regiment - he had authority over his fellows, and at the completion of his training I recommended him for promotion to the rank of corporal, a role where I felt his talents could be expressed. Additionally I felt it better that any authority he held over his peers should be used to serve the purposes of his military superiors, rather than being left unrestrained to possibly work against them.

Though the men were eventually brought to combat readiness, we awaited a theatre of war in which to prove their actual martial mettle. My experience with the Gael had confirmed me in the belief that the Devil does indeed make work for him when his hands are idle, and I was impatient to depart for the scene of some continental engagement before idleness and ennui began to undermine my work with these recruits. In barracks, chattering in erse so that their officer s could not follow, I feared that resentments old, or new-fashioned might surface amongst the Highlanders.

Stirling lies near a large coalfield, which provides the means of existence for many miners. The coalfield also provides the fuel which powers the nearby Carron Iron Works, which in turn is essential to the sinews of our country's martial valour, by its manufacture of the Carronade military artillery. While we were awaiting our order for departure to our as yet unknown destination, a cessation of work occurred amongst the miners around Stirling, in pursuit of some grievance over pay. The strike was accompanied by much violence, as many of the workmen were apparently unwilling to join the strike. Some of the latter were burned in vitriol attacks, and in retaliation one striker was shot and killed by an assailant unknown, but presumed to be of the opposing non-striking party.

At this point the civil magistrates invoked the laws pertaining to workmens' combinations, and declared the strike illegal; as this had no effect, appeal was then made to the officer in command at Stirling, to provide troops to restore order, and protect those workmen who wished to go about their lawful business unmolested. This need for military intervention was felt to be all the greater when some of the workmen began to indicate a more menacing demeanour, by planting a Liberty Tree in the town of Fallin, at which ceremony Caps of Liberty were also worn. French agents were suspected of being at work, though my own view was that merely local grievances were at the root of the mining conflict

Unfortunately, to combat the idleness in which they found themselves, then men had been given occasional leave, and had used the opportunity to repair to the surrounding villages, and had thus become acquainted with members of the mining community, and were privy to the real or imagined grievances which were felt in the pit villages. I stated the opinion to my commanding officer that it would be more prudent to request troops for the purposes of maintaining order from Edinburgh and Glagow, rather than using our own raw Highland recruits, but he overruled my opinion, and ordered that the men present themselves in battle array for action in the villages of the coalfield. A half an hour before muster, I was given a message by my aide de camp that MacPhee wished to speak with me, and I requested that he enter my chambers, and inform me of his business.

The man stood, splendid in his military uniform, and spoke without preamble, words to the following effect, though not exactly to their letter, as I rely on memory,

'The men do not wish to fight with the miners, with whom they feel they have no quarrel. The miners tell us that they were slaves not ten years ago until they won their freedom, which they seek to use to have a fair reward for their labour. We have taken the King's pay and will fight his enemies overseas, my soldiers say, but for all I argue with them, they wish no part in the quarrel between the miners and the authorities.'

I knew at once that, though he posed as their reluctant porte-parole, MacPhee was in fact the spokesmen of his men whose views he shared. There had been several mutinies amongst the Highland troops in Edinburgh, over diverse matters, and here we were threatened with one at Stirling. I dismissed MacPhee, instructed him to continue to enjoin obedience upon his men, and told him to await further orders. It was with the greatest difficulty that I persuaded my military superiors to keep our own Highlanders confined to barracks, whilst requesting military assistance from Glasgow instead. A deciding factor in ensuring this outcome was, I believe, the receipt that very afternoon of orders requiring us to march to a Fife port and embark for Spain in a week's time. A mutiny would have thwarted these necessary plans, and to this day I am certain that MacPhee was somehow privy to these despatches ordering embarkation, and aware of the strong hand which he played with such apparent reluctance.

Once military operations were underway in the Peninsular theatre of operations, I had no cause for complaint about MacPhee. At my instigation he was later promoted to sergeant, which, given his lack of education was the highest point to which he could reasonably aspire in the Army. His bravery in the face of the enemy was exemplary, and he was always the first of his men into action. At the siege of San Sebastian he personally put out of action two enemy gun emplacements single-handed, for which he was decorated. However, it was in another sphere of military operations that he most excelled, and to which he was soon directed.

As is generally known, when invaded by Napoleon, the Spaniards, unable to compete with the French in the field, resorted to a kind of irregular warfare of a most savage but effective kind. Instead of engaging in direct combat, the patriots of that country would attack French supplies, ambush small groups of soldiery, disrupt communications and in this way tie down a large number of the enemy, which would otherwise have been Wellington's responsibility to engage.

In aiding this work, MacPhee was invaluable. His enormous strength and stamina, and the ability learned on his native heath to subsist on next to nothing, allowed him to be a perfect go-between for our forces and the guerillos. With some of his trusted confederates, he passed again and again behind the enemy lines, contacting and living with the irregular forces. Posing as a gipsy on account of his swarthy looks and Erse speech - which the French took as Romany - MacPhee was able to co-ordinate our activities with those of our allies, and to arrange their provision with the physical necessities of warfare, and also with specie. I should mention here that MacPhee never once came under suspicion from myself of appropriating any of the materials he was charged with, for his own usage. Whilst showing MacPhee's good qualities to advantage, these activities fed, however, his weaker side, that is his vanity. He began to conceive of himself as invaluable, and deserving of greater recognition for his services. Whilst I could strive to have him decorated for his valour, and rewarded with bounties for his actions, there was no way I could advance the cause of his promotion further; the man could not read or write, nor had he any inclination of that military science necessary for progress upwards through the ranks.

My commanding officer had continually chided me with being partial to MacPhee, and of being wanting in the imposition of discipline in his regard, this view of his dating from the time the incident at Stirling. This having occasioned a partial capitulation on his part, my commanding officer had always resented the affair as a personal slight against him of the Highlander's authorship. MacPhee's subsequent exemplary conduct had done little to assuage this feeling of my superior, while the Gael's forcefully expressed opinions as to his merits and deserts caused no little irritation when brought to his superior's attention. My commanding officer was, in my opinion, looking for an occasion on which to vent his spleen at MacPhee, and it subsequently arrived.

As I have mentioned, MacPhee was charged, among other things, of posing as a gypsy in order to travel around the country and maintain contact with our irregular allies. One of his tasks was to give these allies money for subsistence, a task he was engaged in on the occasion of which I now speak. However, when he encountered a French patrol which he saw to be carrying out a search of all civilians entering the town to which he had been directed, he cached the hoard of coins in his possession, intending later to return for them. Circumstances however prevented this, and he returned to our camp with neither the money, nor his mission accomplished, though he requested a further opportunity to undertake these tasks immediately, which request I relayed to my commanding officer. The latter dismissed me without reply, though he had undoubtedly registered the contents of my communication.

The men were called out in full military garb, to the parade ground. The commanding officer walked over to MacPhee, and addressed him thus,

'So, MacPhee, you wish an opportunity to regain the money you have doubtless hidden away against your intended departure. Well, you dog of a Highland thief, you shall not have it. What do you say to that?'

MacPhee said nothing, and looked impassively in front of him, which appeared to further enrage his superior. 'You will be clapped in irons to await trial. What do you say to that?'

Again MacPhee moved not a muscle and refrained from reply. Whereupon his superior struck him a blow on the side of the face that would have flattened a man stronger than myself, but again the blow appeared not to have been felt by the Highlander, who stood silent and motionless like a great tree. My commanding officer then turned on his heel, and gave the order to his military escort that MacPhee be arrested.

But MacPhee had felt the insults, and more importantly the humiliating blow given in front of his fellow Highlanders. His dirk was from its holster and plunged into the back of his retreating superior in less time than I have taken to tell of it, and Macphee was off and over the low wall of the parade-ground before any had the presence of mind to react. On orders for pursuit being given, I suspect they were but unenthusiastically followed, and limited to a few shots fired into the air. In the narrow streets of the town, where he had friends and associates from his military work, MacPhee was impossible to find, and he soon vanished completely from our trace, using the skills he had formerly practised for our advantage, to our present disadvantage.

MacPhee is a man of considerable abilities, but he has also suffered from what he conceives of as injustices at the hands of those in power over him. However, that he has deserted from the forces of His Majesty in wartime, and in the course of this that he has also murdered a superior officer, are both capital offences in the face of which I feel it would be both impolitic and useless to plead for mercy. However, I would recommend that in future efforts be made to appoint those to power over the Highland soldiery who are familiar with their manners, or to instruct those who are not so, in the particular ways of the Highlander, in order to avoid the repetition of such misfortunes as the present one, and the too numerous others which have occurred in these wars.

Ian R. Mitchell