Down by the Riverside to St Vincent Crescent by Ian R. Mitchell

This walk from Ian R. Mitchell takes the westender out of his/her usual Byres Road ratruns, to Glasgow's fast-changing riverside, and to Britain's most splendid Victorian crescent outside Bath, celebrating its 150th anniversary. Tradition and change in one stroll.

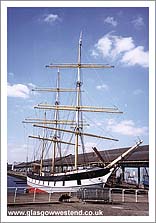

The walk can conveniently start and end at Kelvin Hall Underground Station. Head southwards down Benalder Street and across the River Kelvin to the back of Yorkhill Hospital, where the restored Wheatsheaf Building, a former Partick granary, is now flats. Note the wheatsheaf sculptures on the roof and the old jib hoist. From here turn south (right) down Ferry Road past new flats and a leftwards turn into Yorkhill Park takes you behind Yorkhill Hospital and on to Kelvinhaugh Primary School, built in Victoria's Jubilee in 1887. From here head rightwards downhill along Sandyford Street towards the expressway. (An alternative is to carry on a few yards down Ferry St to the expressway and take the cycle track leftwards alongside it) Either way you end up at the pedestrian expressway flyover and cross, seeing ahead the splendid former Custom House, one of Glasgow's fine Italianate towers, and the mooring of the Glenlee, a nineteenth century cargo sailing ship. 'Glasgow's ship' as the Glenlee is designated, is worth a visit if time permits.

From here the walk is a designated one to and along the Clyde, past the moat house hotel. No tradition here, but stark modernity in the black glass phallic hotel and SECC, Glasgow's copying of the Syndey Opera House. (Glasgow is confident enough to copy anything; across the river is the Grand Old Opry, an answer to Memphis'). Also across the river is the new Science Centre, looking like a dinosaur nesting-site from Jarassic park, and there too will be the future BBC headquarters once a new access bridge is built. Past the now world-famous Finnieston Crane, last used in the early 80s and now a symbol of Glasgow (though it was built in Carlisle) is the City Inn, a rather functional-looking new hotel, but whose splendid food belies its image, and where a riverside terrace, the only one in Glasgow, allows a refreshment stop. A few plant pots and sheltering trees would improve the terrace.

From here all roads lead to St Vincent Crescent, though in complicated ways. One method is to retrace steps your back to the SECC and take the covered (red) pedestrian walkway which crosses the expressway and leads you to Finnieston Station (Now Exhibition Centre). Exit here, turn left and head up Minerva Street, where a left turn takes you into the Crescent which mysteriously starts at no. 19. Another longer route is to continue along the pedestrian walk/cycle track on Lancefield Quay past modern flats on both sides of the river, some looking like the Pyramids, past the stance of the Waverley, (if it is in port, the world's last ocean-going paddle steamer, built in Glasgow in 1947 is a photo-opportunity not to be missed) under the Kingston Bridge, now half an inch west, or east, of where it used to be, and to another building which reminds us we are in granary country. Not an olde-worde one like the Wheatsheaf building, but something that seems as if it should be in the middle of the American Prairies or Chicago, the brick and tile palace of Snodgrass' Grain Mills, still miraculously in operation though doubtless some property developer already has them in his sights as flats. From here you can go back to the SECC and follow the simple route to Finnieston Station, but try this other option instead as a scenic route to the Crescent.

Walk northwards under the Kingston Bridge, on the western side for about a quarter of a mile. Here you are in Lodging House land, but the natives are harmless. At Anderston Station a pedestrian flyover will take you into unfashionable Anderston, but it is worth it. Some fine new housing association flats are mingled with the grim 60s architecture, and the look of the area is softening. This was once tenement land,( and the Buttery, one of Glasgow's traditional restaurants somehow survives in one hereabouts) and at a detached bit of Argyll Street is a wonderful building in Art Nouveau style, a Glasgow Savings Bank, with ornate metal work and a fine coloured mosaic entrance, Sadly, this jewel is in a state of disrepair. Off Byres Road it would be worth millions. Pass this relic, pass the Salvation Army Pyramid and continue along Houldsworth Street, past some semi-derelict nineteenth century warehouse and factory buildings, which have ornate brickwork and are worth restoring, until a PC World is spotted ahead. Turn right into Finnieston Street, and then in a hundred yards or so, at the wrought-iron relics of a former Victorian public toilet at the entrance to Minerva Street, you enter Crescent land, for this street which leads to the Crescent, was part of the original development.

As Glasgow developed in the nineteenth century, and the centre and east became crowded and polluted, the middle classes moved west. On the Stobcross estate was planned a massive development of terraced flats, with pleasure gardens, curling ponds and the like. Minerva Street was built in 1849 in a rather Edinburgh style - note the curved ground floor windows - and then work on the Crescent began, being finally finished in 1851; so 1850 is a convenient middle date for the anniversary. The architect was Alexander Kirkland, who himself lived in a flat in the Crescent. Being the longest crescent in Britain outside Royal in Bath, there was a problem of breaking the mononony. Kirkland did this by its serpentine form, by having pillared porticos at irregular intervals externally, and by having a variety of sizes of living space internally. The houses were occupied by solid middle-class people, and many of them had indwelling servants.

However, the industrialisation of Glasgow moved west, and with the construction of the docks, (now all filled in), a huge railway marshalling yard was built to the south of the Crescent, and the larger housing development dropped, The enclave rapidly became surrounded by factories and tenement properties, and began a gradual decline. By the 1950s the Crescent was blighted by business/office usage and multiple occupancy, and as late as 1970 plans were afoot to demolish the whole area (part of the flanking entrance to Minerva Street was actually demolished). However times changed, people began to see the attractions of living off city centre, off west end, and moved in, and a fight led to restoration in the 1980s, instead of demolition - and A-listed architectural status. One delight of the street in that it must have the highest concentration of bowling greens in the world; three line its southern side, leaving an open outlook to the changing riverfront, and sounds of clicking on a summer's evening.

The Crescent is possibly the most socially mixed area in Glasgow. I often think that if the city has a Grenwich Village, this is it. Many famous people live, or have lived in the Crescent, including John Cairney, Jimmy MacGregor, Daniella Nardini and Sharlene Splitteri, and it attracts freelance artists, writers and the semi-bohemian like. But the Crescent also has many working class residents who moved in when it had lost its earlier middle-class status, and in the street there are sheltered housing and housing association properties. As a contrast to this, we also have a Viscount!

A walk along the Crescent shows you its architectural merit, but don't neglect the cameo of the bowling green gate, a fine example of Possilpark cast iron from 1860. Its south facing aspect makes the Crescent a suntrap, though not all residents have taken so enthusiastically to utilising this as the example illustrated. A Grenwich village, but sadly without the café life. You get out of the dead-end Crescent by retracing your steps to Corunna Street (also a part of the original development, and not in as good condition, with one block already demolished) Round the corner in Argyll Street it is colourful, vif and multi-cultured ( some of the shop fronts could be from Bengal) but the area is still a bit lacking in hostelries other than the traditional Glasgow Pub. The recently restored Ben Nevis on the Corunna St /Argyll Street corner is worth a visit if you want something strong. Otherwise a walk left and west along Argyll Street will eventually take you past the Kelvin Hall to your Subway starting point, with the density of cafes increasing in direct proportion to the proximity to Byres Road. I still like Janssens oppose the Art Gallery, though the nearby Firebird attracts a younger crowd. Don't miss, in the riot of inner-city wildlife of the human variety, (you couldn't) the Argyll Street Elm, which now towers above the tenement building in whose front garden it is rooted. Glasgow's most famous tree.

This walk varies in length according to choice, as there are several route options, corners to explore and places to visit. Taking in every twist and turn it is upwards of four miles, and will take two to three hours without stops.

Copyright I.R. Mitchell

Read about Ian Mitchell