Partick: Glasgow's Girnal

Ian R. Mitchell takes a look at Partick's fascinating history

Such has been the decline of Scots as the lingua franca in Glasgow that not many people would know what a girnal was. The cosmopolitan nature of the city has produced its own argot, which is expressive and creative, but it contains relatively few Scots words. I was surprised on coming here from Aberdeen to find that people didn't know what a brander was, or a scaffie. This, with my support for the Dons, made me feel quite proud of myself. A century ago, most Glasgow folk would still have known that a girnal was a grain chest and that Partick was the area where was landed and processed most of the city's grain.

Partick's Grain Mills

Partick's western border with the city was the River Kelvin, which falls steeply to the Clyde, and which powered the early granaries along its banks. And where today survives the city's last grain mill. This is owned by Rank Hovis and produces flour for their Duke Street bakery. Timothy Pont's map of Lennox c1600 shows a cluster of mills on the lower river, including Bishop's Mill and a meal mill leased by the city of Glasgow. The incorporation of Glasgow bakers also owned two mills on the river, one called the Bunhouse Mill. Although other works, such as spinning and slit mills used the water power of the Kelvin, it was grain mills which predominated.

Large scale industrial flour milling began with the opening of the Scotstoun Mills in the 1840s, though as the Kelvin provided such cheap and efficient power, these were still water-operated, and remained so till the later expansion in the nineteenth century. The Regent Flour mills were built across the Kelvin from the Scotstoun mill in the 1890s. Owned by the SCWS from 1903, this mill made the famous Lofty Peak flour. (The site is now a car park for the Kelvin Hall). This cluster of mills large and small made it logical for the Clyde Navigation Trust to establish its grain depot at Meadowside in Partick in the early 1900s, and until very recently the origin of most material for Glasgow's ubiquitous jeely peece was in the girnals of Partick.

Large scale industrial flour milling began with the opening of the Scotstoun Mills in the 1840s, though as the Kelvin provided such cheap and efficient power, these were still water-operated, and remained so till the later expansion in the nineteenth century. The Regent Flour mills were built across the Kelvin from the Scotstoun mill in the 1890s. Owned by the SCWS from 1903, this mill made the famous Lofty Peak flour. (The site is now a car park for the Kelvin Hall). This cluster of mills large and small made it logical for the Clyde Navigation Trust to establish its grain depot at Meadowside in Partick in the early 1900s, and until very recently the origin of most material for Glasgow's ubiquitous jeely peece was in the girnals of Partick.

A good place to start an exploration of the area is at the bridge over the Kelvin, built to join Partick with Glasgow in 1877, just west of the Kelvin Hall. One end of the bridge bears the Glasgow coat of arms, the other that of Partick - which appropriately has millstones and a wheatsheaf on its crest. Or at least that what many accounts say; I have never found them, so maybe its another urban myth.The previous bridge lies just to the north and is still open to pedestrians. From here a walk down Bunhouse Road, and right along Old Dumbarton Road brings you to the Wheatsheaf Buildings. Now flats this cameo was built in the 1830s on the site of the original Bishop's Mill, and has delightful wheatsheaf motifs carved on its gables. It operated as a mill till the 1960s, and was water driven till the 1950s.

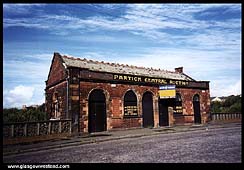

No such new use has been found for the derelict Partick Central station further on, though the land released by demolishing part of the Scotstoun Flour mills is now occcupied by stunning modern flats. Partick is being squeezed between the West End and the Riverside, old and new middle class residential areas. A huge cleared site to the west of Partick Central awaits residential development, as a corridor to connect the riverside to the West End. This was formerly the Partick Foundry and after closure in the 60s became the site of unsightly scrap metal depots. However, back around 1600 this was the site chosen for the building of Partick Castle, a fortified house serving as the country home of George Hutcheson, co-founder of Glasgow Hutcheson's Hospital. Partick Castle was demolished in 1836.

No such new use has been found for the derelict Partick Central station further on, though the land released by demolishing part of the Scotstoun Flour mills is now occcupied by stunning modern flats. Partick is being squeezed between the West End and the Riverside, old and new middle class residential areas. A huge cleared site to the west of Partick Central awaits residential development, as a corridor to connect the riverside to the West End. This was formerly the Partick Foundry and after closure in the 60s became the site of unsightly scrap metal depots. However, back around 1600 this was the site chosen for the building of Partick Castle, a fortified house serving as the country home of George Hutcheson, co-founder of Glasgow Hutcheson's Hospital. Partick Castle was demolished in 1836.

Given its location (West End, University, Kelvingrove Museum etc) and facilities (subway, railway, expressway) Partick has become a classic example of the benefits, or drawbacks depending on your view, of the process of gentrification. It can't be long before the owners of the last operating grain mill realise that they can make a lot more money selling the land for housing than using it to employ millers and make flour. Gentrification promotes de-industrialisation.

Before heading along Beith Street it is worth visiting Glasgow's smallest graveyard. In amongst some modern housing on Keith Street lies the Quaker burial ground. Surrounded with metal railings, it has no gravestones, but a wooden plaque stating its function.

Before heading along Beith Street it is worth visiting Glasgow's smallest graveyard. In amongst some modern housing on Keith Street lies the Quaker burial ground. Surrounded with metal railings, it has no gravestones, but a wooden plaque stating its function.

Society of Friends

Burial Ground

Gifted by

John Purdon 1711

Last used 11-X11-1857

The Quakers gifted the site to Partick, and a part was used for road building-in return for the site being kept in good order (which it appears to be) - and for 1s a year being donated to the Society of Friends. Does the Kooncil still pay the 5p? Apparently Purdon's wife was the first interred in the cemetery, and the family, which was a prominent one in eighteenth century Partick, is commemorated in neighbouring Purdon Street.

The Goat

This area is the heart of the old pre-industrial village of Partick, and Keith Street used to be known as The Goat. The goat in question was not four footed, but an old Scots name for a small burn, one of which ran here. At the north end of The Goat was The Heid o' the Goat, a place where acrobats, quack doctors and religious and political agitators held court. A nineteenth century Partick poet Tom Burns describes the scene,

Though its richt name's in print on a prominent spot

The ane its best kent by is the heid o the Goat

There tradesmen o every class you will find

In guid Doric language expressing their mind

The old cottage buildings here were only demolished in the 1930s, and the Heid o the Goat is now the Comet car park.

Along Beith Street are renovated sandstone tenements and some fine new flats, but the most interesting building is the former Partick Fire Station, dating from 1906. This too has been converted to housing though the brick fire tower has been retained as a feature. The building itself is mostly brick built, unusual for Glasgow pre 1914. and also done in an almost Germanic style of architecture; Potsdam rather than Partick. Just beside the fire station at Meadow Road access is gained to the Clydeside cycletrack, which provides a high and traffic free vantage point for further sightseeing.

Along Beith Street are renovated sandstone tenements and some fine new flats, but the most interesting building is the former Partick Fire Station, dating from 1906. This too has been converted to housing though the brick fire tower has been retained as a feature. The building itself is mostly brick built, unusual for Glasgow pre 1914. and also done in an almost Germanic style of architecture; Potsdam rather than Partick. Just beside the fire station at Meadow Road access is gained to the Clydeside cycletrack, which provides a high and traffic free vantage point for further sightseeing.

The whole skyline to the south is dominated by cranes. But not shipyard cranes as would once have been the case, but building cranes, for the riverside here is the site of a multi-million pound redevelopment, dominated by new housing. Partick was never the shipbuilding centre that Govan was, but it did have some important yards. From the cycletrack, looking back towards the Kelvin's mouth, can still be seen the derelict brick and sandstone offices of the Meadowside Shipbuilding Yard, with its central tower in a sort of French renaissance style. Hopefully this will survive redevelopment in some form. One of the early owners of this yard, David Tod, became the first Provost of Partick. The second provost was John White owner of the Scotstoun Mills, showing the tendency in the nineteenth century for local capitalists to exercise almost feudal powers in their locales, as Provosts, MPs JPs etc.

Across the Kelvin mouth lay Inglis' Pointhouse yard, which specialised in paddle steamers, building the current Waverley in 1947, and the one of the same name which it replaced, which was sunk at Dunkirk in 1940. The Maid of the Loch, currently being refurbished as an attraction at the Loch Lomond National Park, was built by Inglis' in 1952, but the yard closed ten years later, ending shipbuilding on the Kelvin.

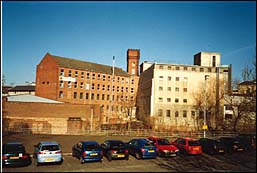

Between Meadowside and Whiteinch to the west, the Partick riverside was dominated by granaries. Inglis yard had a famous set of sheer legs, 96 feet high that stood till 1965, but they were puny beside the 13 storey brick granary built by the Clyde Navigation Trust in 1911-13, at a cost of ?130,000 (which would not pay for half of one of the flats being constructed on its ruins.) Partick Thistle's move to Maryhill in 1909, after over 30 years in Partick, was occasioned by the purchase of their stadium for construction of the granaries. In 1937 another granary, equally large was built adjacent to the original one, and this Meadowside girnal of Glasgow claimed for a while to be one of the world's largest brick buildings. It gave a curiously re-assuring feeling to see its bulk, and many united in opposition to its destruction, arguing that the granary itself could have been converted to housing. Though the developers successfully argued against this, a significant part of the original construction materials were recycled into the new buildings.

Whether these new residents will consider themselves Partickonians remains to be seen. The construction of the Clydeside expressway separated Partick from the River Clyde, and it also cut Partick itself asunder. At the Thornwood Roundabout Dumbarton Road disappears under the Expressway, in a maze of flyovers, to re-emerge in the rather forlorn district of Whiteinch. Few people consider it so today, but from its foundation Whiteinch was part of Partick burgh. Very little was found hereabouts till the Barclay Curle shipyard opened in the 1850s, moving from Anderston. Starting with clippers and ending with liners, and building almost everything else in between Barclay Curle was one of Glasgow's finest shipyards, a specialist builder which even managed to operate fully during the 1930s Depression. The yard has been demolished but the marine engine works Barclay Curle built just before World War One remains, with its fine hammer head crane and the (listed) mansard roof enlivening the skyline.

Whether these new residents will consider themselves Partickonians remains to be seen. The construction of the Clydeside expressway separated Partick from the River Clyde, and it also cut Partick itself asunder. At the Thornwood Roundabout Dumbarton Road disappears under the Expressway, in a maze of flyovers, to re-emerge in the rather forlorn district of Whiteinch. Few people consider it so today, but from its foundation Whiteinch was part of Partick burgh. Very little was found hereabouts till the Barclay Curle shipyard opened in the 1850s, moving from Anderston. Starting with clippers and ending with liners, and building almost everything else in between Barclay Curle was one of Glasgow's finest shipyards, a specialist builder which even managed to operate fully during the 1930s Depression. The yard has been demolished but the marine engine works Barclay Curle built just before World War One remains, with its fine hammer head crane and the (listed) mansard roof enlivening the skyline.

Whiteinch

Whiteinch is, at the moment, rather forlorn, with much brown land and many closed shops, but at one time was almost a model village. South of Dumbarton Road were the tenements for the workers in the shipyard, and to the north were rows of modest villas, Gordon Park, built in the 1880s for workers from the Scotstoun estate. These, clustered round the bowling green, now form a conservation area. Cut off from Partick by the expressway, Whiteinch was also cut off from Victoria Park to the north by the same road, which took over a slice of the park itself. A stroll through the park will not only bring you back to Partick proper, but also allow you to see the world-famous Fossil Grove which it contains. Not just one, but a whole stand of fossilised scale trees, over 250 million years old, with their trunk-like roots, excellently preserved. Again though not generally thought of as Partick today Victoria Park was actually laid out by the burgh.

Thornwood

Thornwood

Renegotiating the over and underpasses of the expressway brings you to the bottom of Thornwood Drive, cursing the negative effects such roads have on urban communities - and on urban pedestrianism. Thornwood has always had the reputation of being the posh part of Partick, and hereabouts reminds me of Dennistoun. Fine red sandstone tenements, well maintained and inhabited by the prosperous and respectable working and lower middle classes. There can be a monotony in respectability but in Thornwood this is broken by some of the best council housing in the city. There are blocks of good municipal housing, and at Crathie Drive a building of exceptional merit and interest which dominates the Thornwood skyline. This is Crathie Court built in 1952, but its art deco features show pre-war design influence in the projecting balconies and lines of porthole windows. Set in well maintained grounds, the building was designed as 88 flats for single people at a time when almost all housing was for the standard nuclear family. In recognition of its importance the building gained a Saltire Award. Crow Road takes us back down to Dumbarton Road, and slightly more scruffy East Partick.

But even here the relentless march of gentrification continues. Up Norval Street off Crow Road generations of Pertick wummen toiled in Tomlinson's factory making cardboard boxes; you could watch then from the passing blue trains at Partick Station. Today its bright pastel exterior and atrium roof proclaim it as The Printworks apartment block.

Riots in Partick, 1875

Moving along Dumbarton Road is a pleasant pedestrian experience, as the line of the street is virtually unbroken and the commercial premises are all occupied and well maintained, in contrast to those in Whiteinch. It was not always so pleasant however, and in 1875 a procession of Irish nationalists on Dumbarton Road was attacked by political opponents, leading to three days of rioting. This was ended only when special constables were sworn in, to support the police in quelling the disturbances. Partick?s other great unrest was in the Rent Strikes of 1915 when the area was one of the strongest in the city for action against profiteering. These struggles were led by the Partick housewives, harrassing the landlords agents with hails of refuse and laying about them with pots and pans. The women in turn were led by I.L.P. member Helen Crawford. The women of Partick appear a fierce brood. A famous nineteenth century Partick lass was Big Rachael, all 6ft 4 inches and 16 stones of her. She worked as a labourer in the Meadowside yard and later as a foreman(person) in a brickworks. In the Riots of 1875 she was enrolled as a special constable.

Before 1914 Partick was a stronghold of Orangeism, especially its shipyards where many had come to work from Ulster; it is not generally recognised that 40% of the city's Irish immigration came from Ulster, and this was largely responsible for bringing the poison of sectarianism to Glasgow. John Paton, in his Proletarian Pilgrimage, writes of his dismay at finding such a phenomenon in Glasgow, so absent in his native Aberdeen. He describes how an ILP propaganda lorry was set ablaze by Orangemen in Partick, and the comrades decided to assert their right of free speech by a march along Dumbarton Road. They were ambushed by well-organised groups emerging from closes to attack the procession, Paton comments,

'We'd no chance at all against them They were tough fellows from the shipyards who enjoyed nothing so much as a good fight. It wasn't a defeat, it was a rout'.

However, even before the war these die hard Tory Orangemen were prepared to listen to socialist speakers, rather than simply attack them. Paton recounts the factory gate meeting at a Whiteinch shipyard (probably Barclay Curle's), addressed by his fellow Aberdonian, Jamie Kessack. Immediately grasping their attention by his opening words,

'Last Sunday I stood on the Custom House steps at Belfast, girdled by the steel of the bayonets of the circle of soldiers who enclosed me.'

Kessack got a "rapt audience and hearty applause at the end." The war and its aftermath seriously weakened, though it did not kill, political Orangeism.

A wee trip off to Dumbarton Road to Burgh Hall Street allows us to take a look at the centre of Partick government from 1852 till 1912. In that latter year an Act of Parliament overturned Partick's wishes to remain independent, and a piper played "Lochaber no More". Would that, a century on, our politicians had the courage to similarly add Glasgow's present periphery to the city. But Partick, Govan and Maryhill were working class areas; Bearsden and Newton Means are not.

Partick Burgh Halls, though well used and being renovated, cannot compete with those of Maryhill and Govan, for example, either in exterior embellishment or interior furnishings. But it certainly had a better view, looking out as it does across the lawns of the West of Scotland Cricket ground to the villas of Partickhill rising beyond. Once a curling pond and bowling green, the site later became the centre of the rather un-Scottish game of cricket, which it remains. It has a place in football history however, in that it hosted the first Scotland England international in 1872. Not only roads and railways can separate social classes, so too can parks, or sports fields, and while at the north end of the cricket ground you are in patrician Partickhill, on the south you are in proletarian Partick. Partick library, which is passed on the right heading back to the Cross, used to have a nice wee exhibition on the history of the area, though it was missing on my last visit.

Glasgow Gaels

Between Gardner Street and Stewartville Street is one of the few cleared areas on Dumbarton Road, where a block of tenements was demolished to make way for a recreation area. This that could be better maintained, and the Friends of Mansfield park are working hard at it. On Stewartville Street, occupying the ground floor of a solid set of tenements built, as it proudly states, by the St. George's Co-operative Society is found the offices of An Commun Ghaidhligand a Gaelic bookshop. It is appropriate that this is located here as Partick has always had a tradition of Gaelic immigrants and Gaelic churches. It is estimated that in Partick and the wider West End of Glasgow there is a greater concentration of Gaelic speakers than anywhere outside Lewis in the Western isles. Though this tradition was swelled by the influx of Gaels to work on various jobs on the Clyde, it goes further back to when Partick was on the drove route into Glasgow from the West Highlands. The drovers came down what is now Crow Road (Crow is from the Gaelic croadh, cattle) and overnighted in Partick before moving into Glasgow. A famous inn, Granny Gibbs, was the destination of these drovers, and lay near the present Thornwood roundabout. This inn was built by her husband in 1796 when droving was at its height, and demolished a century later, when it had ended. Drovers kept their sheep and cattle in her pens, before moving into Glasgow. Her thatched dwelling was commemorated in another of the prolific Partick poets, George Boyce,

The drovers passing east and west

Knew her wee hoose of call

With Highland whisky o the best

She would supply them all.

This tradition of Highland hostelry continues in the pub on the corner of Stewartville Street, the Lismore, which does much to support Gaelic music and culture. The owners have also commissioned a set of fine stained glass windows in the pub, commemorating the Highland Clearances, and showing Highlanders at work. These panels have clearly been influenced by those of Stephen Adam in Maryhill Burgh Halls. Partick's taverns have a long tradition of conviviality. Bunhouse Road is not named after a bakery but after an inn called the Bun and Yill Hoose which formerly stood there. In Strangs Glasgow and its Clubs we read of the Partick Duck Club. This group of Glasgow worthies were mainly from the Trades House, and used to repair to Partick to feast at the Bun Hoose on roast duck and peas, washed down with claret. One of their number was immortalised in the couplet,

The ducks of Partick quack for fear

Crying 'Lord preserve us, there's MacTear!'

The profusion of fat ducks in Partick was due to their feasting on the products and by products of the grain mills on the Kelvin. The old Bunhoose apparently had a lintel dated 1695 over the door, but was demolished in 1849.

Back at the foot of Byres Road we are at Partick Cross. Here is a curious scene. On the one hand good quality red sandstone tenements, and on the other every inch of vacant land being filled with lofts and appartments. On the one hand the spread of up-market restaurants and cafes, on the other the survival of little works, almost sweatshops - and probably the greatest concentration of charity shops in Glasgow. Does this signify a hidden poverty in Partick, or just that the nearby denizens of the more prosperous west-end areas can spot a bargain when they see one? Its worst housing long ago demolished by the expressway Partick does not give out the air of dereliction of certain other inner city working class areas of Glasgow. Its population, which grew form about 5,000 in 1852 to 56,000 in 1912, has declined to about 40,000 today, and is rising again.

The University was never in Partick. But the Western Infirmary, or rather the Anderson College of Medicine as it originally was, did lie within the burgh boundaries, but only just, after the institution was moved from Glasgow in 1889. A dramatic relief by Pittendreich Macgillivray adorns the building, showing doctors performing an operation. He was an Aberdeen artist who did much work in Glasgow. Just within Partick also, and bearing an address in Dumbarton Road, is the curious Tudor Cottage on the north bank of the Kelvin, within Kelvingrove Park. This was an exhibit of model workers' housing from Leverhume's Port Sunlight factory on Merseyside. It was shown at the International Exhibition in Kelvingrove in 1901, and later donated to the city, for use as a park keepers dwelling. This is the last, or first, dwelling in Partick and a good place to end.

The University was never in Partick. But the Western Infirmary, or rather the Anderson College of Medicine as it originally was, did lie within the burgh boundaries, but only just, after the institution was moved from Glasgow in 1889. A dramatic relief by Pittendreich Macgillivray adorns the building, showing doctors performing an operation. He was an Aberdeen artist who did much work in Glasgow. Just within Partick also, and bearing an address in Dumbarton Road, is the curious Tudor Cottage on the north bank of the Kelvin, within Kelvingrove Park. This was an exhibit of model workers' housing from Leverhume's Port Sunlight factory on Merseyside. It was shown at the International Exhibition in Kelvingrove in 1901, and later donated to the city, for use as a park keepers dwelling. This is the last, or first, dwelling in Partick and a good place to end.

In 1912 they played Lochaber no More; such is the rate of change in Partick, as it becomes swallowed up by the West End of Glasgow, that it may soon be Partick No More. Close to the West End, close to the university, close to the Art Gallery, Partick was always that bit different from other working class areas in Glasgow.

Copyright I.R. Mitchell

If you have enjoyed Ian's feature about Partick you may also enjoy:

Walks in Glasgow

also

BBC Alba Partaig about Gaels in Partick