THE PAISLEY PATTERN: POETRY, POVERTY..and PHILANTHROPY

Ian R Mitchell finds that for the Buddies, charity possibly begins at home.

Ian R Mitchell finds that for the Buddies, charity possibly begins at home.

As an Aberdonian living in Glasgow, and often accused of the same sin, I can empathise with the inhabitants of Paisley, known as Buddies, who are often accused of meanness. People who will "Pick your pocket for a penny", rather than being "Buddies willing to spare a dime", is how Glasgwegians or the burghers of neighbouring Renfrew see them. But more than this empathy born of a stigma draws me often to Paisley.

Of all the multitude of satellite towns round my adoptive Glasgow, it is Paisley which I find the most interesting. It has a fascinating 1000 years history, almost as long as Glasgow's, and, for a town of 75,000 people, a very rich built environment which recalls that history. Whether mean or no, the Buddies are certainly a cocksure lot with a good conceit of themselves and their town, and not without reason. In fact being regarded as "Glasgow's most interesting satellite" they would probably regard as an insult to their own perceived high status. An eminent, but mis-informed, visitor to the town in the 1870s was famously informed by an irate Town Council that "Paisley is NOT a suburb of Glasgow."

Remember that and you will be welcome.

Buddies are also more reserved than Glasgwegians, a little suspicious of "Ootlanders" and have a deserved reputation for clannishness. "May you die in Paisley" was an old blessing here. In Paisley, there is little of the gallus street theatre and constant banter of Glasgow, where in 10 minutes you can become a man's best friend. And here again, in their reserve, Buddies remind me of my native Aberdonians. One possible explanation for this, is that most of Paisley's population were recruited from neighbouring Lanarkshire, Renfrew and Ayrshire. From being a small Scottish town, Paisley became a large Scottish town. In 1900 only 5% of Paisley's population was Irish born, and 1% Highland born, compared to five times that number in neighbouring Glasgow.

Buddies are also more reserved than Glasgwegians, a little suspicious of "Ootlanders" and have a deserved reputation for clannishness. "May you die in Paisley" was an old blessing here. In Paisley, there is little of the gallus street theatre and constant banter of Glasgow, where in 10 minutes you can become a man's best friend. And here again, in their reserve, Buddies remind me of my native Aberdonians. One possible explanation for this, is that most of Paisley's population were recruited from neighbouring Lanarkshire, Renfrew and Ayrshire. From being a small Scottish town, Paisley became a large Scottish town. In 1900 only 5% of Paisley's population was Irish born, and 1% Highland born, compared to five times that number in neighbouring Glasgow.

If they carried over the small town Scottish reserve to Scotland's biggest town, why are Paisley folk called "Buddies"? The word has nothing to do with the familiar Americanism, meaning close friend. The term was in use by the early nineteenth century when writers spoke of Paisley "bodies", the old Scottish word here simply meaning people, or folk. Pronounced as "buddies" (as in "Gin a body meet a body" (Coming Through the Rye.), the term has struck, and is now spelt as it sounds.

A quarter of an hour from Glasgow Central and you arrive at Paisley Gilmour Street, a fine mock-Tudor castellated building, with the platforms on a raised viaduct. If you look carefully around at platform level, behind the grime you will see much of the nineteenth century wood and ironwork still intact, only awaiting a lick of paint to make it stunning. Why do we not treat our Cathedrals of Transport as they deserve? The Gothic revival Post Office of 1892, just outside the station on County Square has fared better, being converted to a pub and restaurant, and its red sandstone exterior is still in fine condition. On the south side of the square a late eighteenth century terrace only needs some cosmetic work to be a delightful cameo. Nothing short of demolition, however, could improve the ghastly shopping centre making up the fourth side of the square. Till 1971 the site was occupied by the town's nineteenth century jail and courthouse.

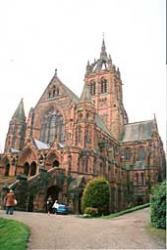

Paisley itself has no cathedral, but on emerging from the station and going down Gilmour Street to the Cross, the eye is inevitably caught, across the waters of the White Cart, by the 800 year old Paisley Abbey, a visual delight in exterior and interior. A church has been here since the Celtic monastery associated with St Mirin, and later a priory and then the abbey was founded in the 13th century. The Norman foundation was partly destroyed by the English in the wars of independence and in 1553 the tower collapsed. Though continuing as Paisley parish church, the present abbey is to a great extent a late nineteenth and twentieth century reconstruction by eminent architects such as Anderson and Lorimer.

Paisley itself has no cathedral, but on emerging from the station and going down Gilmour Street to the Cross, the eye is inevitably caught, across the waters of the White Cart, by the 800 year old Paisley Abbey, a visual delight in exterior and interior. A church has been here since the Celtic monastery associated with St Mirin, and later a priory and then the abbey was founded in the 13th century. The Norman foundation was partly destroyed by the English in the wars of independence and in 1553 the tower collapsed. Though continuing as Paisley parish church, the present abbey is to a great extent a late nineteenth and twentieth century reconstruction by eminent architects such as Anderson and Lorimer.

The west door is the main Norman relic, and the nave the main medieval one, and inside is the 8th century Barochan Cross, and a frieze of carved panels illustrating the life of St Mirin. The abbey hosts frequent concerts by the excellent Abbey Choir. The adjacent Place (ie Palace) of Paisley survived the Reformation and was a mansion house and then a slum dwelling, and for a while public house, before restoration. In this restoration streets of densely packed slums, which had blocked out the abbey, were demolished to create the open vista of today.

Though founded as an ecclesiastical centre, it was the development of the textile industry in the eighteenth and even more nineteenth centuries, that made Paisley world famous and for a while Scotland's third largest centre of population after Glasgow and Edinburgh. Just south of the Abbey at the Hammills waterfall on the Cart, stands the imposing bulk of one of Paisley's former mills, now sympathetically converted into flats. This was the Anchor Mill, which was founded in 1812 by the Clark family, to harness the power of the Cart and the mill underwent continuing expansion for almost a century. Here was first produced thread wound on wooden spools, of the kind which I can still remember from my childhood days. These spools or bobbins were recyclable, and when returned brought a halfpenny off the price of a new reel of cotton thread.

By 1870 Paisley was described as "the dirtiest and most unhealthy town in Scotland" and rather more favourably another observer commented, "The town was full of smoky grime and industrial vigour, drunker squalour and puritanical religion." It was one of the fastest growing towns in the whole of the United Kingdom, prompting the Tory Prime Minister Disraeli to comment "Keep your eye on Paisley". But it was poor. In the 1820s hand loom weavers could earn over £1.00 a week, but the weekly wage for a female in the thread mills in the 1870s was less than half of that.

Just west of the Abbey is found the Clark Town Hall, which must be the most imposing example of such a structure of any town in Scotland. Fitting indeed, though since continually failing in its efforts to become a city, Paisley is Scotland's largest town. The burgh's population peaked at around 1970 at 90,000, but like other industrial towns in recent decades, has lost population, and now has 75,000 inhabitants. The town hall was built in 1882, helped by £20,000 of funds provided by the Clark family, whose name graces the building, and the famous sculptor Mossman's statue of George Clark stands outside. Further marble busts of members of the Clark family are found at the entrance to the Town Hall. It was not just money these entrepreneurs were after, but immortality! And in the days before death duty and inheritance tax, such sums were petty cash. The Clarks' bequest to the Town Hall was less than 3% of the fortune John Clark left in his will in 1894.

Still in use for social functions, the Clark Town Hall's role has been transferred to the quite ghastly Renfrew Council Offices to the east of the Abbey. Around the area of the Town Hall and Cross are what must stand as the largest collection of public sculptures in Scotland outside of Glasgow and Edinburgh city centres. As well as those of the Clarks mentioned, are the statues of luminaries of the Coats dynasty by Rhind at the northern end of Dunn Square, as well as the obligatory one of Queen Victoria in the square itself. An excellent short leaflet is available on these, and the other public sculptures of Paisley, from the Tourist Information Office in Gilmour Street.

But the Buddies have not neglected recognition for their town's less affluent citizens. In Abbey Close Paisley's greatest weaver poet Robert Tannahill is commemorated in this open air sculpture park, as is the less well known Alexander Wilson. Less well known in Scotland that is, than in the USA, where the self-educated weaver emigrated and became regarded as the founder of North American ornithology. A memorial frieze commemorates Wilson's childhood playground at the Hammills.

But the Buddies have not neglected recognition for their town's less affluent citizens. In Abbey Close Paisley's greatest weaver poet Robert Tannahill is commemorated in this open air sculpture park, as is the less well known Alexander Wilson. Less well known in Scotland that is, than in the USA, where the self-educated weaver emigrated and became regarded as the founder of North American ornithology. A memorial frieze commemorates Wilson's childhood playground at the Hammills.

Tannahill's fate was less happy. He killed himself when his poetry failed to extricate him for the drudgery of the loom. The melancholy cast of his mind is evident in many of his poems.

Keen blaws the wind o'er the braes o' Gleniffer

The auld castle's turrets are covered wi' snaw

How changed fae the time when I met wi' my lover

Amang the brume bushes by Stanely green shaw.

His cottage lies a little to the west of the town centre, on Queen Street, a place of pilgrimage for his devotees, as well as the meeting place of the Paisley Burns Club, which Tannahill founded in 1805. Formerly "thackit" the cottage is now slated. Tannahill's best known poem is probably, "Will ye go, lassie, go?"

Before the coming of factory methods of production, Paisley was a centre of hand loom weaving. Versatile, the "wabsters" could turn their hand to linen, silk, or cotton. Their fame was recorded by Burns, when he dressed the graveyard temptress in Tam o Shanter in "Her cutty sark, o Paisley harn". Like many of their bretheren, the Paisley weavers were radicals in politics and religion, but to an even greater extent, were given to composing poetry. Radicalism and Paisley went together: possibly because Paisley remained, until comparatively recently, one of the poorest towns in Scotland. (Poverty maybe also the source of the Buddies alleged meanness.) As one local rhymster put it,

Paisley's name is widely spread

And history doth show it's

Been famed alike for shawls and thread,

For poverty and poets.

The Paisley weavers were a radical lot, given to strikes and rioting in defense of their wages long before the ideas of the ideas of French Revolution came along. The weavers, educated and intelligent, adopted those ideas to a man. As Alexander Wilson put it,

The Rights of man are noo well kenned

And read by many a hunder

And Tammy Paine the buik has penned

And lent the Court a lounder. (=severe blow).

Wilson escaped to America when powerful local dignitaries were offended by his writings, and also escaped from the loom, which he did not love. One book of his poems was called Groans from the Loom.

In 1819 there was a week's rioting in Paisley High Street as the authorities tried to suppress demonstrations in favour of parliamentary reform, and in the Radical War of 1820 nowhere was more radical than Paisley, when thousands of local workers went on strike and some went as far as to take up arms for political reform. In a series of treason trials in that year in the town, the defendants were acquitted. Paisley's radicalism continued into the Chartist period in the 1830s and 40s, when a surprising local leader of the agitation to gain working men the vote was the Rev. Partick Brewster. His denunciations of the rich and powerful at a time when poverty was endemic and cholera rampant, meant he was passed over for the post of main minister at the Abbey when it became vacant.

The weaving part of Paisley's industrial history is commemorated in the Sma' Shot Cottages in Shuttle Street, just a short walk from the Town Hall, which show how the weavers lived and worked. The most scenic route is along Forbes Place, by the side of the Cart, and then by Causeyside and New Streets. (At the entry to New Street it is worth stopping to admire the Russell Institute, another charitable endowment "to buddies from a buddy"- one Mrs Russell. Built in 1923 as a child clinic by local architect James Maitland, it is probably Paisley's greatest twentieth century building. Dawson's sculptures of mothers and children complement this Beaux Art masterpiece. Today it is a family planning centre.)

No such social welfare was available for the weavers in the sma' shot cottages, whose lives can be relived on Wednesdays and Saturdays afternoons in the summer months. In their restored form these are very picturesque buildings, but the life of the weaver became harder and harder as the nineteenth century progressed. Faced with the competition from factory production and power driven Jaquard looms from the 1830s, the hand-loom weaver worked longer and longer hours for less and less pay. In 1832 Cobbet said "the weavers of Paisley are covered in rags and half-starved." There were 7,000 in the 1830s, but less than 100 hand-loom weavers in 1900.

Just close by the Sma Shot cottages lies Paisley Arts Centre, in a converted church, the old Laigh ( or low) Kirk, which was Paisley's second kirk after the Abbey itself. This was the Paisley charge of John Witherspoon before he went to America and became the principal of Princeton Presbyterian College in 1768. Witherspoon is more famous as being the only clergyman to sign the US Declaration of independence, in 1776. Though he was not a Buddy by birth, Paisley is milking Witherspoon for all his worth, and a huge statue of the theologian has recently been erected outside Paisley University, which has established links with Princeton University through the Witherspoon connection.

Witherspoon Street takes you to Storie Street and then a left turn along Wellmeadow Street lands you in front of the imposing bronze cast monument to Paisley's adoptive son. Executed by Alexander Stoddart, Paisley cunningly gifted a copy of the sculpture to Princeton. Who says Buddies are mean? Interestingly, Witherspoon left Paisley after his attempts to reform the morals of the population had largely failed, and even landed him in court on a libel charge.

Stoddart is also in the process of executing a sculpture of Paisley's prodigal son, Willie Gallacher, legendary figure of the Red Clydeside era and Communist MP for West Fife. Gallacher was born in Paisley, but spent most of his life in political struggles in Glasgow, where he was a prominent figure in the Clyde Workers Committee and the strikes during World War One, and thereafter his work amongst the Fife miners resulted in his becoming their MP in 1935. Though spending most of his active life away from Paisley, Gallacher returned to the town, and died in a council flat in 1965. Forty thousand people followed his coffin, draped in the red flag to Woodside Crematorium. Stoddart has also been commissioned to commemorate another local Buddy, Thomas Tait the architect, and one of Britain's foremost in the 20th century. He was responsible for St Andrew's House in Edinburgh , and Tait's Tower at the Glasgow 1938 Empire Exhibition. But to return to our promenade.

On the other side of Wellmeadow Street from Witherspoon's statue, we can see more examples of Paisley philanthropy, rather than Paisley parsimony. The Museum and Art Gallery, funded by contributions from the town's wealthy textile capitalists, especially the Coats, lies across from the University, as does the Thomas Coats Memorial Church of 1894, paid for by the family and notable more for its vast bulk - the size of many a cathedral - rather than any great architectural quality, in my opinion. But it made sure that the Buddies would never forget the Coats. Surprisingly for Presbyterian Paisley, Thomas Coates was a Baptist, and this is a Baptist church.

Thomas Coats died in 1883, and was followed by his great rival John Clark in 1894. Competition between the firms gave way to price fixing as time went by and then came amalgamation, when Coats swallowed up the Clarks concern in 1896. Further expansion and acquisitions followed, and by 1913 Coats was Britain's largest textile company, capitalised at almost £8 million, and employing 40,000 workers worldwide - only 12,000 of these in Scotland. Indeed, it was one of the first multi-nationals, operating in Russia, the USA and Spain.

Thomas Coats died in 1883, and was followed by his great rival John Clark in 1894. Competition between the firms gave way to price fixing as time went by and then came amalgamation, when Coats swallowed up the Clarks concern in 1896. Further expansion and acquisitions followed, and by 1913 Coats was Britain's largest textile company, capitalised at almost £8 million, and employing 40,000 workers worldwide - only 12,000 of these in Scotland. Indeed, it was one of the first multi-nationals, operating in Russia, the USA and Spain.

In 1910 Coats profits were £3.2 million, bigger than the profits of the second (Imperial Tobacco) and third (Guinness brewers) most profitable British industrial companies combined. The Coats had a mansion in Ferguslie, an estate at Glentanar on Deeside, and a collection of yachts, one a 500ft steam driven one. To their lucky 40,000 shareholders they were paying a staggering 25% annual dividend in the early twentieth century. But what about the workers, I hear you ask? That 40,000 were not so lucky, those in Paisley for example, mostly living on less than £1.00 a week.

The Coats, like the Clarks, were paternalistic employers. As well as giving generously to charity, they also supported sickness and pension schemes for their workers. But they paid low wages, and with a largely female and non-unionised labour force, were able to get away with this for almost the first century of their existence as a firm. In the early years of the twentieth century this paternalistic consensus began to break down. In 1904 1,000 boys at the mill went on strike, and the following year 3,000 of the mill girls followed suit. These were disorganised actions, with little effect. But in 1907 many had been alerted to the plight of the mill workers, and several prominent outsiders, such as Keir Hardie the I.L.P. member of parliament, and trades union organisers were active, earning the fierce denunciations of the Coats family, including Thomas Glen Coats who was Paisley's Liberal M.P. at that time.

In 1907, the bulk of the workers at the Anchor Mill, 4,000 strong came out, and decided to march of the Ferguslie Mill and bring out their fellows. There followed a blockade of Ferguslie, with the police defending it from the strikers and preventing their entry. The police with difficulty retained control, and one reason for their problems was the novel method the mill lassies had of close combat. Realising their physical weakness against burly policemen, they would remove their hat pins and contact some delicate party of a policeman's anatomy. Coats cleverly gave the entire Ferguslie workforce time off on full pay during the strike, to prevent them joining it. Eventutally the isolated Anchor workers went back to work, having won some concessions. But a century of paternalism and workers' loyalty to their Liberal employers was gradually coming to an end.

In the early twentieth century Paisley was still one of Scotland's poorest towns, with almost 50% of the population living in officially overcrowded accommodation and infant mortality rates of 100 per 1,000 twice the Scottish average. And dominated by textiles and female labour, it was a low wage economy still. People imagine textiles as a nineteenth century industry, but Paisley's reign as thread capital of the world lasted much longer. Indeed in 1950, the Anchor and Ferguslie works employed more than 10,000 people between them, more than they had ever employed in the Victorian era, and even in the 1960s there were still 5,000 at Coats Paton as it was then called. This was not much less than the new giant car plant at Linwood on Paisley's outskirts, then the main local employer. But in less than a generation, both old and new industries have vanished.

Paisley has weathered the virtual collapse of Scottish manufacturing industry better than many West of Scotland towns. One sign of this is that Paisley is the only location outside Scotland's cities which continues to produce a daily newspaper, the Paisley Daily Express, which has appeared since 1874 and still sells over 10,000 daily. The University, created in 1992 from an amalgamation of various institutes of higher education, helps, as does the proximity of the region's biggest private employer, Glasgow Airport.

But as we go west from the University, Wellmeadow Street bears unmistakable scenes of urban decay - though the main area of urban deprivation in the town, Ferguslie Park, with 45% of the population economically inactive, lies outside the city centre. A sharp turn up West Brae appears initially to give us more of the same, in a series of semi derelict buildings, but in the space of a hundred yards we are in a different world, the world of Oakshaw, one of the most delightful and interesting streetscapes in Scotland, and with one of the best views.

Ascending West Brae, a large cupola'd building is evident. Though known irreverently by the Buddies as "The Parritch Pot" due to its (inverted) shape, this is Paisley's nineteenth century architectural masterpiece, built 1849-52 by Charles Wilson who was the architect of much of Glasgow's prestige Park Circus area. Again it is a product of Paisley philanthropy, the John Neilson Institution being built as a school after a £22,000 bequest by a local grocer of that name. It was meant for children of the poor and orphans, and provided food and clothing as well as education. Some in Glasgow felt Paisley was getting above itself, hiring such an eminent architect to build the Institution, and "erecting a palace where a poorhouse would have been more to the purpose." (Hugh MacDonald Rambles round Glasgow) 1854.

Now flats, the Institution building is not accessible, but a walk round it to the belvedere at Oakshawhead gives a fine view of the building and on a clear day, north to the Campsies and Ben Lomond. Although it is true that many of Paisley's finest buildings post date the writing of MacDonald's book, it is surprising to find him, who visited Oakshaw, commenting, "In general architectural appearance the town of Paisley presents few features calling for the particular attention of the tourist." That's Glasgow for ye, the Buddies would say.

Oakshaw Street is an eclectic mix of architectural sytles and periods. There is housing of recent construction alongside eighteenth century religious buildings, such as the Old Manse, and the Gaelic Chapel of 1793. There are staid nineteenth century tenements beside flamboyant revivalist buildings of the same century like the Brough Nursing Home, and on each side of the street enticing cobbled lanes lead downwards to hidden corners calling for exploration. There is the Paisley Philosophical Institution rooms ( and Camera Club) and the splendidly spired Oakshaw Trinity Church, one of the last of the many kirks here still in use.

And as ever there are examples of Paisley benevolence, of charity beginning at home. The Hutcheson Charity school flourished in the nineteenth century till the pupils were transferred to the more palatial premises of the John Neilson. And, of all things, the street hosts an observatory, the Coats Observatory, gifted by Thomas Coats in 1883 but now run by Paisley Museums-and still functioning. This building is one of the first wheelchair friendly (with ramp access) ones ever constructed, as Thomas Coats who was astronomically-minded, was himself confined to a wheelchair later in life.

And as ever there are examples of Paisley benevolence, of charity beginning at home. The Hutcheson Charity school flourished in the nineteenth century till the pupils were transferred to the more palatial premises of the John Neilson. And, of all things, the street hosts an observatory, the Coats Observatory, gifted by Thomas Coats in 1883 but now run by Paisley Museums-and still functioning. This building is one of the first wheelchair friendly (with ramp access) ones ever constructed, as Thomas Coats who was astronomically-minded, was himself confined to a wheelchair later in life.

Dropping down Oakshaw Street east to School Wynd brings you back to County Square and the rail station. If time permits and the body demands sustenance, a walk along High Street and down New Street to the Bull Inn will land you in a pub which claims-with some justification- to be the best Art Nouveau hostelry in the country, though I can think of a couple of rivals in Glasgow. This will also allow a study of the fine-if somewhat faded-glories of some of the buildings in the High Street, such as the YMCA building and the Liberal Club. Built in 1886 the latter expressed the domination of nineteenth century Paisley by Liberalism, in the way that the twentieth century was to become dominated by Labourism, Paisley electing its first Labour M.P. in 1924. The labour movement has, however, left fewer memorials than its predecessor, apart from the fine Co-Operative building in Causeyside Street. And Willie Gallacher's statue-when it is finally built.

I am unsure whether I have acquitted the Buddies of meanness; but I hope I have convicted their town of fascination. Its name is mainly known worldwide from the Paisley Pattern, the teardrop design made famous by the Paisley Shawl. But the shawl era was a fairly short one in the town's history, largely over by the 1870s, and that industry never dominated the town in the way thread making did. Though you can go and see the world's largest collection of shawls in the local Museum, the pattern of Paisley embraces much more than the world's most famous design.

Copyright I.R. Mitchell