Easterhouse, Altered Images - Ian R. Mitchell

About Ian R. Mitchell and other articles

April, 2008

April, 2008

What images does the word conjure up when you hear it? Gangs, Ice Cream Wars, drugs, poor housing, poverty, unemployment, and "a desert wi windaes" as Billy Connolly described Drumchapel, Easterhouse's sister scheme across on the other side of the city of Glasgow? I say "images", since it is almost certain that unless you live in Easterhouse, you will probably never have been there. The scheme is by-passed by all major roads and rail links, and has little employment to draw in outsiders. And the only place where Easterhouse features in the media is in the Bad News section.

I would never deny that these commonly-held images are ones which resonate with the reality of Easterhouse, though often in a very exaggerated manner. This is Easterhouse, not Rio or Jo'burg, for heaven's sake! But there are other realities here, and it is time that the message is got across that Easterhouse is "More Than Just A Scheme", as the sub-title of a local history project, carried out by the Trondra Group, put it.

* What about history, culture, education and the arts for alternative images of Easterhouse? You have heard all the bad news, to hear something different, read on.

At its height, Easterhouse was Western Europe's largest social housing project, and like many a "best laid scheme", which seemed a good idea at the time, it alas, was to "gang agley". After World War Two there was a demand for social justice, and housing figured prominently in this demand. Nowhere else was this more so than in Glasgow, which had some of the worst and most overcrowded housing in Europe: parts of the city had population densities close to those of Calcutta. The idea was to shift the population off to healthier locations in the suburbs, where houses with baths, toilets and gardens would replace the old slums. One of the new residents from the 1950s recalled, "Two bedrooms, a living room and a separate kitchen. And a bathroom! It seemed like a palace to me." Kids would have fresh air, and be able to play in the countryside, rather than rat infested back courts.

The problem with Easterhouse, and with Glasgow's other satellite schemes, was that, although they were as big as the New Towns being built, they were not New Towns. Instead of being overseen by centrally funded, government-underwritten New Town Development bodies, they were financed by a pretty impoverished Glasgow Corporation. This could build the houses, but had little money, and few powers, to direct infrastructure to the schemes. Consider the following.

By the early 1960s Greater Easterhouse had in excess of 40,000 people, more than present day Perth or Inverness. There were three doctors' and one dentist's practice. There was one library, built in that year. No swimming pool, no cinema. There were no banks (even in 1990 one cash machine served 30,000 people). There was no police station. There were almost no shops, only (expensive) vans which came round the doors. There was little public transport, in an area where car ownership is still very low, and was then was almost non-existent. Most of all there was not a great amount of local work, except for those lucky enough to gain employment at the small Queenslie industrial estate, where companies like Weir's pumps with 900 workers and Olivetti, with 1000 employees making typewriters in the 1960s, were the largest employers. One ex worker at Olivetti recalled, "I really enjoyed it. There was a brilliant sense of cameraderie, and the pay was good."

But most people in Easterhouse had to commute long distances (at a cost) to their former workplaces, just as for many years, with inadequate schooling provision, many kids were bussed back to their old slum schools. Mothers took the bus (expensive and time consuming) back to Shettleston or Bridgeton in Glasgow's East End to do their shopping, fathers went back to pubs and clubs there. Many people thus found their disposable incomes reduced.

Worse still, it became apparent that the materials the houses had been built with (concrete blocks, metal window frames etc) made them cold, damp and very expensive to heat. The housing stock began to deteriorate faster than the old tenements had done, and soon large parts of the scheme were impossible to let.

...our new homes were upmarket compared to the slums we came from. We now had electricity, an indoor bath and our own bedrooms. But it didn't take long before these houses were as bad as the ones we came from due to dampness of the walls and condensation on the windows. They cost more to heat that the old slums.

When the economic recession of the 1980s came along, most of the factories in the Queenslie estate, such as Olivetti and Weir's, closed their doors. The trickle of people from schemes like Easterhouse became a flood, and population plummeted. By 1990 Easterhouse had so bad a reputation that the philanthropic entrepreneur Antita Rodick, known for her poverty initiatives, diverted her attention from the Third World, and set up a Body Shop factory in Easterhouse, whose needs were deemed to be as great. It was in the 80s and 90s the drugs came to Easterhouse, and these fuelled the notorious Ice Cream Wars of the time. A dream died in Easterhouse. But things are changing, new dreams, possibly more realisable, are being created, and the outside world should be told about them, and people encouraged to go and see for themselves.

When Glasgow acquired the area from Lanarkshire in the 1930s, Greater Easterhouse was a scattering of mining and small industrial villages around the Monkland Canal which connected the iron deposits of Lanarkshire with Glasgow's industry. The canal was still open when Easterhouse was built and it provided an outdoor playground, through a dangerous one, for the local kids, who hung swings from the bridges and made rafts to navigate the canal course. One resident recalls, "A pal of mine drowned in the canal, he had wellingtons on and he just slipped in and went under." The canal was in filled in the early 1970s, and the M8 motorway built over its course. The area was also known for its many small landed estates with associated mansion houses, after which many of Easterhouse's sub-divisions are today named. Most of these villages and mansions disappeared with the unfolding of the Easterhouse plan.

When Glasgow acquired the area from Lanarkshire in the 1930s, Greater Easterhouse was a scattering of mining and small industrial villages around the Monkland Canal which connected the iron deposits of Lanarkshire with Glasgow's industry. The canal was still open when Easterhouse was built and it provided an outdoor playground, through a dangerous one, for the local kids, who hung swings from the bridges and made rafts to navigate the canal course. One resident recalls, "A pal of mine drowned in the canal, he had wellingtons on and he just slipped in and went under." The canal was in filled in the early 1970s, and the M8 motorway built over its course. The area was also known for its many small landed estates with associated mansion houses, after which many of Easterhouse's sub-divisions are today named. Most of these villages and mansions disappeared with the unfolding of the Easterhouse plan.

Provan Hall

But not one, it remains. The oldest and the best, the historically unique Provan Hall, still stands, and is at the heart of the Easterhouse community, connected with many initiatives. And yet - financial restraints still mean it is.......closed at weekends! If you cant get out during the week, a great way to see Provan Hall-and Easterhouse's other attractions - is to get the free bus from George Square which City Glasgow Council provides on Doors Open Day in September every year, and this does a drop/ on drop off service including Provan Hall. This is the best place to start as it is the oldest house in Easterhouse, indeed, as the locals will proudly tell you, it is (possibly- depending on sources used), the oldest house in Glasgow and without doubt the finest pre-Reformation mansion house in Scotland. Yet I have still to find many of my Glasgwegian associates, never mind outsiders, who know Provan Hall is even there.

Provan Hall dates from about 1460. The Prebendary of Provan was associated with Glasgow Cathedral, and James IV hunted in the woods around when he was a canon of the cathedral. Mary Queen of Scots is reputed to have stayed at Provan Hall when visiting her sick husband in Glasgow, and there is a local well reputed to be Mary's Well, where she supposedly watered her horse. The original hall has a dairy and kitchen downstairs, the latter with a fine vaulted roof and a fireplace capable of roasting a whole ox. Upstairs are the dining quarters and bedchamber. The curtain wall was added during the troubled times of the 17th century when the then owner Robert Hamilton, an ardent royalist needed help against the local staunchly Covenanting population. The house later passed to a Tobacco Lord, James Buchanan, who remodelled the Hall according to his plantation in the West Indies, including Blochairn House, which today forms the southern part of the Hall. Buchanan's descendants, the Mather brothers were born in the hall and died there as its last occupants in 1934.

But Provan Hall is not just about history, it is about now. The house passed to the National Trust in the 1930s, but very little was done with it subsequently. It is only in the last few years, with management taken over by Glasgow City Council, that the hall has begun to flourish again. Extensive and expensive repairs have been carried out to the building and the grounds landscaped and developed as a wild life oasis. Schools regularly visit the building, and took part in a pageant to commemorate the 500th anniversary of the marriage of James IV to Mary Tudor in 2003. There is an active local history group, the Trondra Group already mentioned, based on the hall, as well as a volunteer gardening group which works on the grounds and the vegetable garden. (Details on opening times and activities 0141 771 4994).

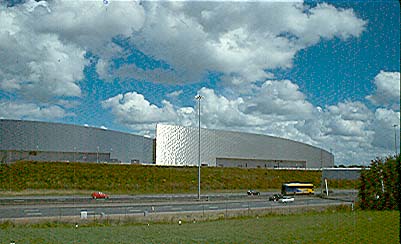

The Fort

It always strikes me as sad when visiting Provan Hall, that there are so few people there. Especially when just outside of the Hall's grounds, thousands of people are visiting the new Fort shopping centre. Though no devotee of the new secular religion of shopping, I am a great admirer of the dramatic architecture of this titanium-clad Fort building. However, it would be nice if some of the shoppers took the short stroll, or even drove, round to Provan Hall to see what else Easterhouse has to offer. Could the owners and occupiers of the Fort not give something back to Easterhouse by directing people to Provan Hall?

Bishop's Loch

The other great secret asset of Easterhouse in Bishop's Loch, and a ramble to there from Provan Hall gives a good impression of the changes taking place in the area. Walking along Auchinlea Road you can see both the old 50s housing, often in disrepair or derelict, and the renovated housing of today. Some housing is restored as social housing, and some has been sold as low cost owner occupier units. In Auchinlea Road you also come across the things they omitted to put into the scheme when it was built; a Sports Centre and a Health Centre. Westerhouse Road takes you past the Township centre, a rather insipid 70s style complex, and to the recently-opened and much more striking John Wheatley College. This is an annex of the mother college in Glasgow's East End, and is named after John Wheatley, the Shettleston-born local M.P. in the 1920s, who as Minister for Housing in the first Labour Government laid the basis for the provision of a social housing policy in his Housing Act of 1924.

The other great secret asset of Easterhouse in Bishop's Loch, and a ramble to there from Provan Hall gives a good impression of the changes taking place in the area. Walking along Auchinlea Road you can see both the old 50s housing, often in disrepair or derelict, and the renovated housing of today. Some housing is restored as social housing, and some has been sold as low cost owner occupier units. In Auchinlea Road you also come across the things they omitted to put into the scheme when it was built; a Sports Centre and a Health Centre. Westerhouse Road takes you past the Township centre, a rather insipid 70s style complex, and to the recently-opened and much more striking John Wheatley College. This is an annex of the mother college in Glasgow's East End, and is named after John Wheatley, the Shettleston-born local M.P. in the 1920s, who as Minister for Housing in the first Labour Government laid the basis for the provision of a social housing policy in his Housing Act of 1924.

The Bridge

Not only original architectural thinking went into this building, but original social thinking. It was placed here as an annex of the main college in Shettleston to make it easier for local people to attend, but the college has also doubled up as a one stop shopping place with Easterhouse Library and swimming pool, which are located in the building. The theatre located in the college complex is used for courses with media students, and also duplicates this function for public arts performances by Platform Arts. In keeping with its aims, the whole complex is called The Bridge. I never thought I would see the day when I went to Easterhouse to see and hear Stravinsky'sSoldiers Tale, but it has happened. The National Theatre of Scotland Young Company is based here, which caused much mutterings in certain circles, but is a venture which deserves support. After all, Easterhouse has already produced Lord of the Rings star Billy Boyd from its ranks. ( Details at events at the Bridge can be had from 0141 276 9696).

A trip to the Bridge at night in winter is a strong recommendation. Then you can see the megaliths of Greater Easterhouse, Cranhill and Garthamlock Water Towers, illuminated like some spaceships from Mars just landed. Cranhill water Tower is also the location of a sensory garden, created by local schoolchildren. These illuminations have added a great deal of cheer to the areas around, especially on dark winter's nights.

Down Lochend Road and Auchengill Road one sees the same combination of regeneration and degeneration in the housing stock, until you suddenly leave Easterhouse and Glasgow behind, at the stunning Bishop Loch. Easterhouse is surrounded by lovely countryside, of little use till now as dumping grounds and drinking dens. That too is changing. The City Council, in collaboration with the Forestry Commission has spent a lot of time and effort and money in developing, way, marking and maintaining a set of trails in the Greater Easterhouse area, and their leaflet The Woodlands of Easterhouse is astonishing in revealing the amount of woodland and loch scenery there is in and around the scheme. Local rangers lead regular walks, and work with local schoolkids in getting them active and out into the countryside.

Down Lochend Road and Auchengill Road one sees the same combination of regeneration and degeneration in the housing stock, until you suddenly leave Easterhouse and Glasgow behind, at the stunning Bishop Loch. Easterhouse is surrounded by lovely countryside, of little use till now as dumping grounds and drinking dens. That too is changing. The City Council, in collaboration with the Forestry Commission has spent a lot of time and effort and money in developing, way, marking and maintaining a set of trails in the Greater Easterhouse area, and their leaflet The Woodlands of Easterhouse is astonishing in revealing the amount of woodland and loch scenery there is in and around the scheme. Local rangers lead regular walks, and work with local schoolkids in getting them active and out into the countryside.

From Bishop Loch there is a waymarked train through Craigend Wood that will take you back to Easterhouse township centre, or there is the possibility of following the western edge of the loch to the former Gartloch Hospital, whose towers loom tantalisingly across the loch from Easterhouse. This was opened in 1890 as one of the main mental hospitals for Glasgow, and continued as such till the mid 1990s, when closure led to gradual decay in the building. Now the hospital is being restored as luxury flats. These may be beyond the income of the residents of Easterhouse, but at least they will be within Glasgow's boundaries and contribute to the city's tax base.

There is a long way to go in Easterhouse. But finally, after half a century, Easterhouse is possibly a more pleasant place to live than many of the areas from which its inhabitants originally came.

*Hidden Histories; Greater Easterhouse, More than Just a Scheme. Trondra History Group 2002. Aside from the personal encounters, all quotations from Easterhouse residents come from this work.