The internment of an Italian from Glasgow.

Strained Loyalties

Strained Loyalties

This article was taken from Tanya's University dissertation. It is about her Italian grandfather being interned on the Isle of Man during World War Two.

No going back

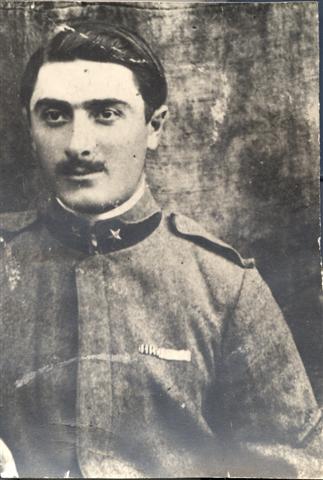

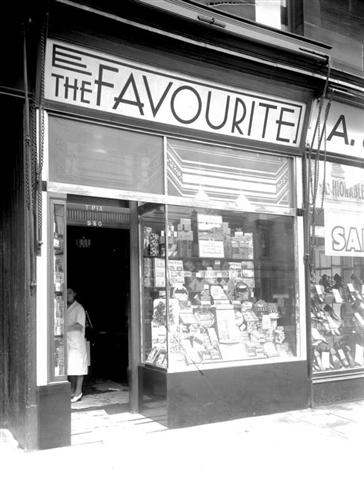

Tommaso Pia, was my ?nonno? (my grandfather). He was born into poverty in the Abruzzo region of Italy in 1895. Like thousands of other Italian men in the immediate post war years of 1920-21 he sought to escape the poverty of his homeland and emigrated to Scotland. A success both in business and at home his new life did indeed bring a degree of wealth that could not have been achieved in the Italy of the 1920s and 30s. He built up a successful caf? business in the Maryhill area of Glasgow and had three daughters, the youngest of whom was my mother.

A Sense Of Distance

He died in 1960 some 11 years before I was born. In my early childhood the sketched outline I had of him was shaped by some faded black and white photographs and the anecdotes passed down by aging family members. I would visit his resting place in a rundown cemetery in Glasgow a couple of times a year and stare at his inlaid photograph on the headstone. The photograph of him, taken in about 1920, only served to reinforce the sense of distance between the two of us. As I grew older, however, history became one of my passions and it was this passion that started to transform these faded images. I began to appreciate the wider social and political environments he would have experienced outside the photographic studio. One particular period held a special fascination for me, his ?internment? on the Isle of Man as an ?enemy alien? in 1940. The deeper I delved into the various political and cultural dimensions of internment the more I could sense what had shaped the slightly resigned expression that I saw in later post war photographs.

Communities Of The Regions

By the time of his internment in 1940 my grandfather had been in Scotland for 20 years. He was one of about 5500 ?migr?s from the Italian peninsula living and working in Scotland. It would be wrong, however, to label this an Italian community. During the inter war years the concept of Italy, a nation only since 1872, was still fragile and local allegiances still predominated. Tommaso came, for instance, from the small town of Picinisco in the Abruzzo region in the south of Italy. Despite a population of only a few thousand it was emigration from this area that would eventually account for about half of the total emigration to Scotland alongside those from the more northern town of Barga in Tuscany. These regional groupings tended to be replicated in Scotland in terms of daily contacts and friendships. The prevalence of regional dialects at the time also influenced the practical make up of these groups and networks.

A Sense Of Place

Ironically, it was Mussolini, back in Italy, during the 20s and 30s who made a concerted effort to cultivate a sense of ?place? and belonging for those, like my grandfather, who had emigrated. He was the first Italian leader to reach out to the various Italian immigrant populations around the world. In one sense, it could be suggested, he politicised emigration by giving direct financial support to the establishment of local Fascist Clubs. While membership, on the face of it, was voluntary it was only by joining that Italians abroad could have any claim to diplomatic or consular protection. Social and cultural activities, however, quickly dominated the activities of these clubs. Holidays to Italy were organised for the children of immigrants and local language classes were established so that the ?mother tongue? could be learnt. One contemporary architect of the internment policy, William Cavendish-Bentick, who chaired the Joint Intelligence Committee, commented in 1940 that the Fascist clubs in Britain were, ?nothing more than the equivalent of the British Society in a South American capital?.

Fair Play And Xenophobia

My nonno was arrested at the family home in Glasgow in the early hours of June 12th 1940 just two days after Mussolini had declared war on Britain and France. The policeman that carried out the arrest was a well known customer of the caf? and apologised for having to make the arrest. Despite the apology, Tommaso spend the next three and half years of his life on the Isle of Man. During my research of this period I came to realise that there had been an initial attempt to underpin the internment policy with an element of British fair play. However, elements of muddle and confusion quickly set in and before long, driven by media led xenophobia; the arbitrary edict of ?collar the lot‟ was implemented. As early as October 1939 internment tribunals had begun to hear the cases of German and Austrians living in Britain. There were three categories that these tribunals would assign to individuals. Category A were deemed an immediate risk to be interned at once. Category B was assigned to those whose loyalty was suspect. While they could remain at liberty they were subject to certain restrictions. For the remainder a Category C meant, that in the eyes of the tribunals, they posed no risk and were able to remain at liberty. With these tribunals dealing with over 70000 cases there was understandable inconsistency with applying this classification system. Some tribunals, such as those held in Leeds, resulted in a majority being classified as Category B while in Manchester most were identified as Category C.

By the time of Italy?s entry to the war in June 1940 the mechanics of the internment policy were clearly strained. During several visits to the records office at Kew in London I began to get a flavour of the confusion that surrounded the policy. Contemporary records suggested that the Foreign Office was clear where some of the blame was to lie. This was particularly pointed in the area of the identifying and classifying Italian fascists and anti fascists. One permanent secretary, in a memo of June 28th 1940, suggested that, ?MI5 cannot help us sort out the sheep from the goats...with them it is a question of hit or miss?. As with the tribunal system attempts to adopt an equitable classification system quickly broke down in the weeks following Italy?s entry to the war. On the 10th of July it was decided that a policy of general internment had to be adopted. This effectively implemented Churchill?s instruction to ?collar the lot? which he had issued to the Ministry of Home Security on June 11th 1940 just a day after Italy?s entry to the War.

The Press Pack

I was intrigued to discover that even in 1940 the role of the media had been severely criticised. In the weeks and months leading up to June 1940 there had been a growing campaign of press hostility towards Italians living in Britain. In April of that year, for instance, the Daily Mirror wrote that each Italian in Britain was, ?an indigestible unit of population? and posed a serious threat to national security. It was against this background that the Labour MP, Rhys Davis, in a commons debate on the 22nd August 1940 lamented how an admittedly flawed selection process had given way to wholesale internment stating, ?the press howled intern the lot and the Government succumbed...that is a lesson to us all not to follow the dictates of the newspapers?.

While the popular press, led by Daily Mirror and Daily Mail, was castigated for its pack mentality, noted caution could be observed among other publications on the issue of internment. A leader writer in The Spectator, for instance, suggested that, ?I would wager that if and when a spy is caught, he will not be found among the enemy aliens examined by the tribunals?. The Daily Express suggested that the internment policy was reminiscent of the witch hunts in 17th century New England while a leader in The Times on the 23rd of April 1940 stated that the alien problem called for ceaseless vigilance but not, ?the wholesale internment imposed during the last war?.

Creating Public Opinion

Thanks to the pioneering contemporary social survey inquiry, Mass Observation, it is possible to gauge the impact of the press during the spring and summer of 1940. The survey was carried out to measure general attitudes towards the issue of aliens under the then umbrella term of the ?Fifth Column?. Reporting in April 1940 it stated that the majority of Britons did not even know what the phrase meant. Detailed interviews in London and the west coast of Scotland revealed that less than one person in a hundred suggested that aliens ought to be interned en masse. When the survey was repeated in middle of May, however, weeks of intensive press campaigning had clearly had an impact with the survey?s author, Tom Harrison, suggesting in the New Statesman of July 1940 that, ?many people who a month before were inclined to be tolerant of aliens were now almost pogrom minded?.

A Camp, Not A Holiday

The largest numbers of internees, including my Grandfather, were ?housed? on the Isle of Man which had been designated a prison island with space for over 10000 internees. The island camps consisted of terraced streets of peace time boarding houses surrounded by barbed wire fences. The camps were designated almost on class lines with ?Onchan? camp housing the wholesalers, hotel and restaurant owners while my Grandfathers camp in Ramsey was mainly for those fish and chip proprietors and owners of small cafes. In addition to Italians and, ironically German Jews, there were also a small number of Scottish, Welsh and Irish nationalists.

The day to day routine within these camps varied little. The alarm would sound at 7am and after physical exercise breakfast would be taken communally in the camps. There would be regular parades and escorted walks out of the barbed wire confines along the Douglas front. While the temptation is to conjure up a 'Dad's Army‟ type image of Private Walker taking fish and chip orders for the internees this would belie the realities within the camps. There was no furniture, towels and very little soap and toilet paper in these camps. Nearly half the men interned were over fifty with many in poor health. Feelings of uselessness and boredom were constant which often led to depression and, in some cases, suicide.

Back On Civvy Street

My Grandfather was released from the Isle of Man in January 1944, some six months after Mussolini had been deposed and Italy had joined the allied forces. During his time away my grandmother, mother and aunts had maintained the caf? business in Maryhill. It had been one of the few Italian cafes in the area to escape from the mob vandalism that was visited on a number of Italian properties in the days following Mussolini?s declaration of war. In the pre counselling days of the 1940s his time on the Isle of Man became a void. Up until his death in 1960 my Grandfather would never speak about his time in Douglas except to say that in times of extreme hunger they were often forced to eat grass. His memories of the time were firmly locked away with the key remaining on the Isle of Man.

My Grandfather was released from the Isle of Man in January 1944, some six months after Mussolini had been deposed and Italy had joined the allied forces. During his time away my grandmother, mother and aunts had maintained the caf? business in Maryhill. It had been one of the few Italian cafes in the area to escape from the mob vandalism that was visited on a number of Italian properties in the days following Mussolini?s declaration of war. In the pre counselling days of the 1940s his time on the Isle of Man became a void. Up until his death in 1960 my Grandfather would never speak about his time in Douglas except to say that in times of extreme hunger they were often forced to eat grass. His memories of the time were firmly locked away with the key remaining on the Isle of Man.

By the time he started working in the Caf? again there were American troops based in the nearby Maryhill barracks. My mother used to remember them coming into the caf? with powdered chocolate so that my Grandfather could make them chocolate ice cream. This he did but in the same breath he would also refuse to serve the odd GI Joe with a reluctance to take the only spare seat in the caf? beside a fellow American who happened to be black. The caf? continued to do well for the family. The fact that cigarettes were not rationed had sustained it through the austere war years while the 1950s saw chocolate coming ?off the ration? which was good news for caf? owners. By the time of his death in 1960 at the age of 65 my grandfather had spent the majority of those years living and working in Scotland and just over 3 years as a interned ?enemy alien? on the Isle of Man.

Distant Voices, Same Debate

Almost 90 years after my grandfather left for his new life in Scotland, I completed the circle by moving permanently to the picturesque town of Citt? Della Pieve in Umbria, the green heart of Italy. Like many 2nd, 3rd and 4th generation Scots Italians I have always shared that sense of ?otherness? that immigrant populations will often speak of. Although English was my first language it was accompanied by Mediterranean gesticulations and a kitchen table overflowing with Italian fare, much of it made by my mother?s hand. From this personal and historical perspective how do I view my Grandfather's internment in 1940?

From a historical perspective my research helped me to realise that, unlike the black and white photos I had of him, the political and cultural landscape around 1940 was coloured with various shades of opinion. Moreover, the debates and issues being raised in Parliament and the wider media were, in many respects, very modern. Behind the edict of ?collar the lot? there were a number of reasoned and dissenting voices raised that touched on complex issues of personal identity, loyalty and justice that are just as relevant in today?s world.

While today?s generation of politicians tie themselves in knots trying to determine what it is to be ?British?, the realities of wartime Britain seems to bring an added lucidity to this debate. Writing in 1940, Francois Lafitte, a researcher with the Institute for Social and Economic Research and fierce opponent of the internment policy, wrote that, ?the real aliens are the Nazis of the soul of all countries...our real friends are not to be judged by tests of birthplace or language but by their present conduct?. Similarly the Labour MP William Wedgwood Benn suggested in a Commons debate on the 22nd of August 1940 that the, ?only aliens are the people who believe in the Nazi form of religion? and that this could not be determined by country of birth.

A Dignified Silence

It may be interesting to speculate how many people may be unaware that their own future liberty may be dependant on the type of debates that occupied the press and the commons in the spring and summer of 1940. Although many of the voices were reasoned they were soon drowned out by media led xenophobia. From a very personal perspective my interest in history and subsequent research on the internment policy has allowed me to glimpse, albeit briefly, behind those photographs that I have of my Grandfather. I have come to realize that it is not a resigned expression I see in these post war photographs but one of dignified silence.

Tanya Starrett 2011.